Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is one of the most significant figures in the history of Western art, particularly renowned for his engravings, woodcuts, and innovative painting techniques. A German artist of the Northern Renaissance, Dürer elevated printmaking to a level of artistic and intellectual sophistication previously associated mainly with painting and sculpture. His engravings are not only masterpieces of technical precision but also profound explorations of religion, science, nature, and human psychology. Through his art, Dürer bridged the traditions of Northern European detail and realism with the theoretical and aesthetic ideals of the Italian Renaissance, creating a body of work that profoundly influenced European art for centuries.

Albrecht Dürer was born in Nuremberg, a thriving center of commerce, humanism, and craftsmanship in late fifteenth-century Germany. His father was a goldsmith, and this early exposure to metalwork had a lasting impact on Dürer’s approach to art. The discipline of goldsmithing demanded precision, patience, and an understanding of fine detail—qualities that later became hallmarks of Dürer engravings. As a young man, Dürer apprenticed under the painter and printmaker Michael Wolgemut, where he learned the fundamentals of woodcut design and panel painting. This dual training in painting and printmaking gave him a unique advantage, allowing him to move fluidly between media throughout his career.

Dürer engravings represent one of the highest achievements in the history of printmaking. Engraving, as a technique, involves incising lines into a metal plate—usually copper—with a burin. Ink is then rubbed into the grooves, the surface wiped clean, and damp paper pressed onto the plate to transfer the image. The process is unforgiving; every line must be deliberate, as mistakes are extremely difficult to correct. Dürer mastered this demanding medium with extraordinary skill, developing a range of line types—thin, thick, curved, cross-hatched, and parallel—that allowed him to create subtle gradations of tone, texture, and light.

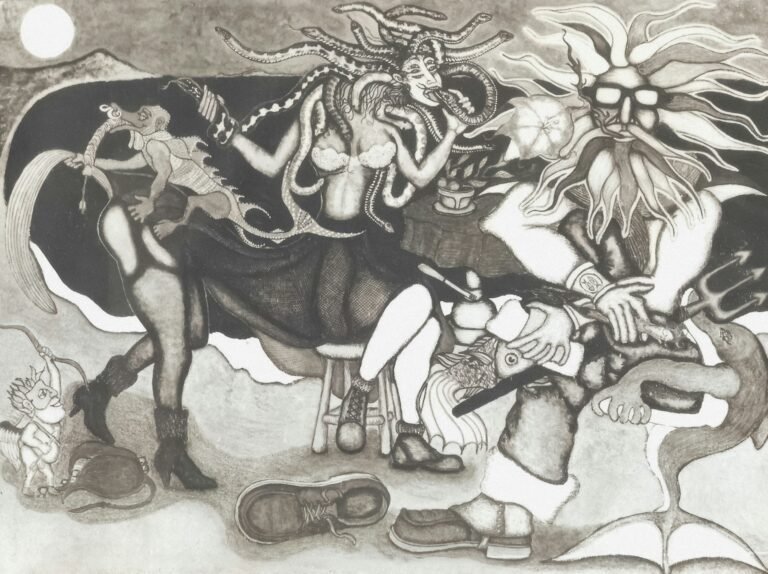

One of the most remarkable aspects of Dürer engravings is their level of detail and complexity. Works such as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), Melencolia I (1514), and St. Jerome in His Study (1514), often referred to as his “Master Engravings,” demonstrate his ability to combine technical virtuosity with deep symbolic meaning. In Knight, Death, and the Devil, Dürer uses dense cross-hatching to create dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, enhancing the somber and moralistic tone of the scene. The armored knight rides steadfastly forward, while allegorical figures of death and evil surround him, suggesting themes of moral fortitude and spiritual perseverance.

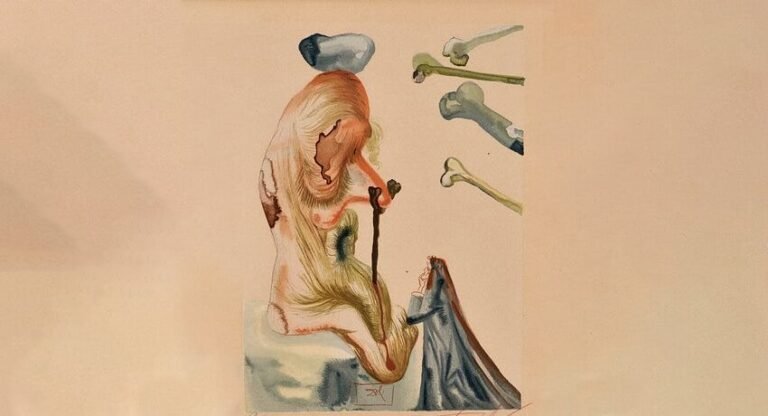

In Melencolia I, Dürer explores the intellectual and emotional state associated with creative genius. The engraving depicts a winged female figure seated in contemplation, surrounded by mathematical instruments, a polyhedron, and other symbols of knowledge and craftsmanship. The meticulous rendering of objects demonstrates Dürer’s technical control, while the complex iconography reflects Renaissance debates about creativity, melancholy, and the limits of human reason. The engraving’s tonal richness is achieved through intricate networks of lines that modulate light and shadow with remarkable subtlety, giving the image a sense of depth and psychological intensity.

Dürer’s approach to engraving was revolutionary because he treated the medium not merely as a means of reproduction but as a primary artistic form. Before Dürer, engravings were often valued mainly for their ability to disseminate images cheaply and widely. Dürer, however, saw printmaking as an intellectual and creative endeavor equal to painting. He signed his prints prominently with his distinctive monogram “AD,” asserting authorship and artistic identity at a time when many printmakers remained anonymous. This practice helped establish the modern concept of the artist as an individual creative genius.

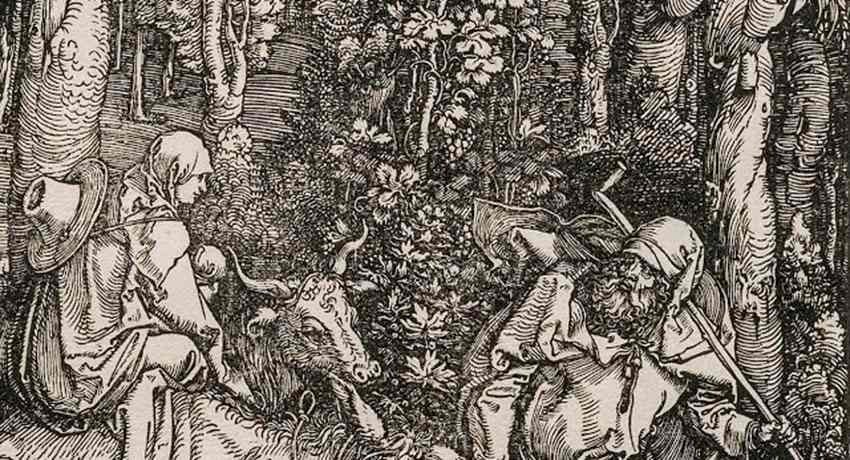

Woodcut was another printmaking technique in which Dürer excelled. Unlike engraving, which involves cutting into metal, woodcut is a relief process in which the artist carves away areas of a wooden block, leaving the raised surface to be inked. Although woodcut traditionally allowed for less detail than engraving, Dürer transformed the medium through innovative design and collaboration with skilled block cutters. His series The Apocalypse (1498) is a landmark in the history of printmaking. These dramatic images, illustrating scenes from the Book of Revelation, are characterized by bold compositions, dynamic movement, and expressive line work.

In The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Dürer creates a powerful sense of motion and chaos as the riders surge diagonally across the composition, trampling humanity beneath them. The strong contrasts between black and white enhance the dramatic impact, while the dense patterns of lines convey texture and depth. Dürer’s woodcuts demonstrate his exceptional ability to adapt his artistic vision to the technical constraints of the medium, turning limitations into expressive strengths.

Beyond printmaking, Dürer was also a highly accomplished painter. His painting techniques reflect a synthesis of Northern European traditions and Italian Renaissance innovations. Northern painting, especially in the Netherlands and Germany, emphasized meticulous detail, rich textures, and oil painting techniques that allowed for subtle color transitions. Italian Renaissance art, by contrast, focused on linear perspective, idealized proportions, and classical harmony. Dürer absorbed both traditions and combined them in a unique and influential style.

Oil painting was central to Dürer’s practice, and he used the medium to achieve remarkable precision and luminosity. His early self-portraits, such as the Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight (1500), demonstrate his mastery of oil technique and his interest in realism and symbolism. In this painting, Dürer depicts himself frontally, with symmetrical composition and a dark background that emphasizes his face and hands. The fine rendering of hair, skin, and fabric shows his Northern attention to detail, while the monumental pose and self-assured gaze reflect Italian ideals of dignity and classical balance.

Dürer’s use of glazing—a technique involving the application of thin, transparent layers of paint—allowed him to build depth and richness of color. By layering translucent pigments over a carefully prepared underpainting, he achieved subtle variations in tone and a luminous surface. This method was particularly effective in rendering flesh tones and fabrics, giving his paintings a lifelike quality. The careful modulation of light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro, further enhanced the three-dimensionality of his figures.

Perspective and proportion were major concerns for Dürer, especially after his travels to Italy. During his visits to Venice and other Italian cities, he encountered the works of artists such as Giovanni Bellini and studied the mathematical principles underlying Renaissance art. Dürer became deeply interested in geometry and anatomy, believing that beauty could be understood through mathematical ratios. This belief is evident in his paintings, where figures are carefully constructed and placed within coherent spatial environments.

Dürer’s fascination with proportion extended beyond practice into theory. He wrote treatises on measurement, geometry, and human proportions, aiming to provide artists with a scientific foundation for their work. These writings reflect his conviction that art was not merely a craft but an intellectual discipline grounded in reason and observation. His theoretical interests also influenced his engravings, where complex spatial constructions and carefully balanced compositions are common.

Nature played a central role in Dürer’s art, and his techniques reveal an extraordinary capacity for observation. His watercolor studies, such as The Large Piece of Turf and Young Hare, are celebrated for their realism and sensitivity. In these works, Dürer employed delicate brushwork and subtle color variations to capture the textures and forms of natural subjects. Although these watercolors differ technically from his engravings and oil paintings, they share the same underlying commitment to precision and truth to nature.

In his religious paintings, Dürer combined technical excellence with emotional depth. Works like The Adoration of the Magi and The Four Apostles demonstrate his ability to convey spiritual themes through expressive gestures, thoughtful compositions, and symbolic detail. In The Four Apostles, Dürer portrays the figures with monumental presence, using strong contrasts of light and dark to emphasize their authority and moral gravity. The inscriptions and symbolic attributes reinforce the didactic purpose of the painting, reflecting the religious tensions of the Reformation period.

Dürer engraving techniques influenced his painting, and vice versa. His understanding of line, developed through engraving, contributed to the clarity and precision of his painted forms. Conversely, his painterly sense of light and volume informed the way he used line in prints to suggest three-dimensionality. This cross-fertilization between media is one of the defining features of his artistic practice.

The cultural and historical context of Dürer’s work is essential to understanding his techniques. Living at a time of profound social, religious, and intellectual change, Dürer engaged with humanism, the Reformation, and the rise of scientific inquiry. His art reflects these currents through its emphasis on individual experience, moral responsibility, and empirical observation. His engravings, widely circulated across Europe, played a crucial role in spreading Renaissance ideas beyond Italy.

Dürer’s legacy in engraving is particularly enduring. Later artists, including Rembrandt, Goya, and even modern printmakers, admired and learned from his mastery of line and tone. His ability to convey complex ideas through black-and-white imagery set a standard that remains influential today. In painting, his synthesis of Northern and Italian techniques helped shape the development of German Renaissance art and established a model for artistic innovation rooted in both tradition and experimentation.

In conclusion, Albrecht Dürer stands as a pivotal figure in the history of art, celebrated especially for his engravings and painting techniques. Dürer engravings demonstrate unparalleled technical skill, intellectual depth, and expressive power, transforming printmaking into a respected and influential art form. His painting techniques reveal a sophisticated understanding of oil medium, perspective, proportion, and color, shaped by both Northern European realism and Italian Renaissance theory. Through his art and writings, Dürer redefined the role of the artist as both craftsman and thinker, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire artists and scholars alike.