In the world of drawing and visual art, few concepts are as fundamental, powerful, and transformative as value—the degree of lightness or darkness of a color or tone. Value scale in art is the backbone of realistic representation because it defines form, creates contrast, produces a sense of space, and guides the viewer’s eye through an artwork. At the center of this principle lies the value scale in art, a structured range of tones that artists use to understand, practice, and apply value relationships. When people refer to the “range in the value scale in art,” they are generally speaking about the full spectrum of tones from pure white to deep black, and all the intermediate grays between them. But the concept is far richer than this simple description. The value scale in art represents a philosophical, perceptual, and technical foundation of drawing, influencing everything from shading to composition and emotional expression. Understanding its full range is essential for artists who want to elevate their work from flat, symbolic depictions to convincing forms with volume, depth, and atmosphere.

At its most basic level, the value scale in art consists of a series of stepped tones arranged from light to dark. Artists often work with five, nine, or eleven-step scales, though some advanced scales include many more gradations. The lightest end, often represented as pure white, symbolizes the complete presence of light; the darkest end, pure black, symbolizes its total absence. Between these extremes are varying degrees of gray, each distinguished by incremental changes in darkness or lightness. These steps help artists identify, replicate, and manipulate the tonal transitions that occur on an object under light. But the scale is not just a technical chart—it is a mental model for interpreting visual reality. Observing the world in terms of value allows artists to “see like an artist,” filtering out distracting colors and surface details to focus on the interplay of light and shadow that gives objects their structure.

One of the most important characteristics of the value scale in art is its range, which refers to the spread between the lightest and darkest values. A broad or high-contrast range uses the full span from white to black, resulting in a dramatic, bold composition. A narrow or low-contrast range, on the other hand, keeps values clustered within a limited section of the scale, creating subtlety, softness, and sometimes mystery. The range chosen by an artist affects not only technical rendering but also mood, meaning, and viewer engagement. Understanding how wide or narrow a value range can be—and how to control it intentionally—is a hallmark of mature artistic skill.

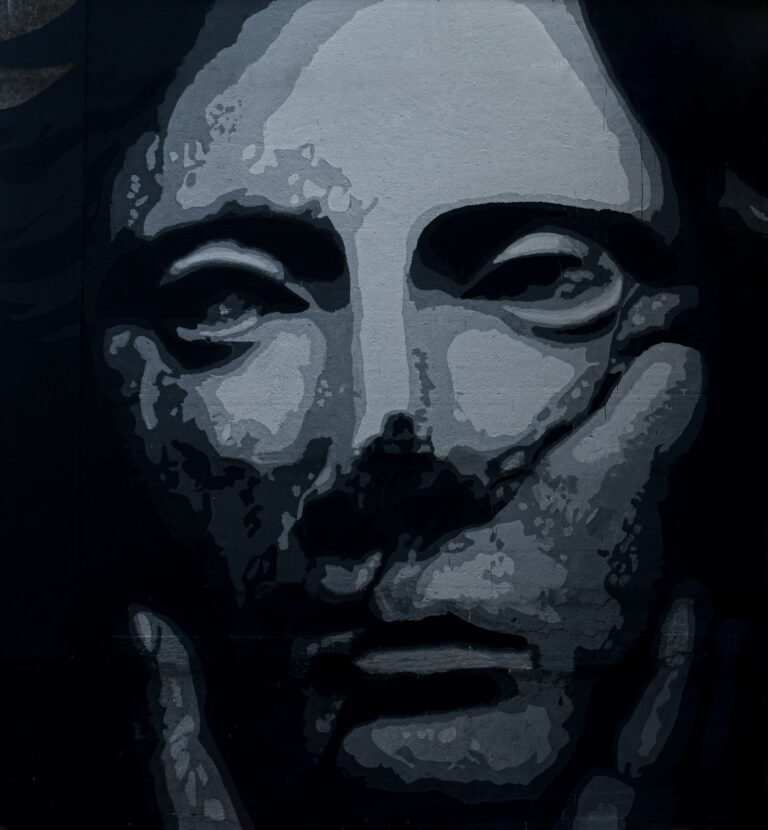

To appreciate how the value scale in art functions, it is useful to consider its historical role in art. Before the introduction of color theory, classical artists relied heavily on value to model form. During the Renaissance, for example, masters like Leonardo da Vinci used value contrasts to create the illusion of three-dimensionality on a flat surface. His famous technique, sfumato, depended on the gentle gradation and subtle blending of values to produce soft transitions and lifelike faces. In Baroque art, Caravaggio expanded the value scale in art’s expressive potential through chiaroscuro, which exploited the stark contrast between light and dark to heighten drama and emotional intensity. These artistic movements illustrate that the range in the value scale in art is not merely a technical tool; it is deeply embedded in artistic tradition and expression.

When artists speak about a “full value range,” they usually mean using values from the lightest possible highlight to the darkest possible shadow in one composition. This range creates a powerful sense of dynamic lighting and three-dimensional realism. For example, in still life drawing, the brightest highlight on a reflective surface may approach pure white, while the deepest cast shadow might approach pure black. Between them, the artist must interpret and recreate the intermediary tones—the midtones, halftones, core shadows, and reflected lights—that define the form, curvature, and texture of the subject. A drawing that lacks these variations tends to appear flat, unfinished, or stylistically limited.

The midtones—the values in the middle of the scale—play a crucial role in tying the composition together. They serve as the connective tissue between the extremes of highlight and shadow. Without carefully observed midtones, an artwork may contain high contrast but lack smooth transitions, making the forms appear harsh or overly simplified. Midtones often occupy the largest proportion of surface area on any object because they represent areas that receive neither direct illumination nor deep shadow. Learning how to manipulate midtones is essential for achieving realism and subtlety.

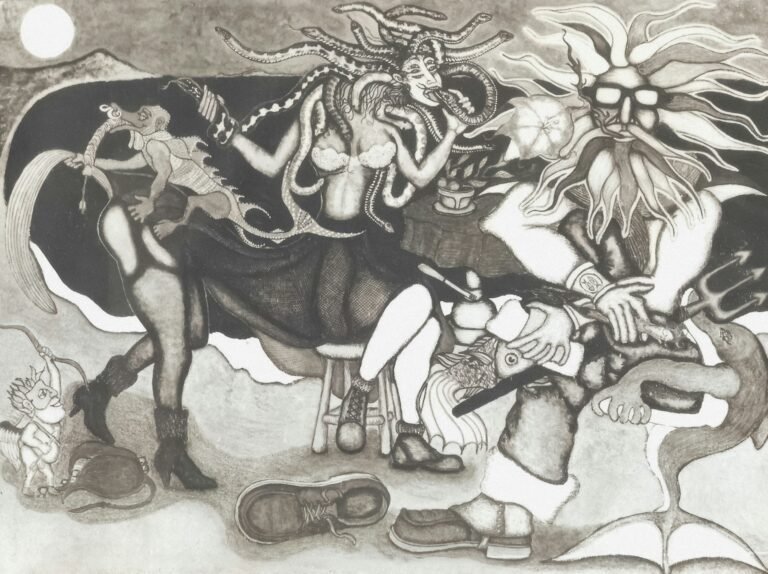

Another important idea related to the value scale in art is value keying—the overall area of the scale that the majority of tones fall into. Artists can “key” a drawing to a high, middle, or low value range, depending on the mood or lighting scenario. A high-key drawing uses mostly light values and minimal dark tones, producing an airy, gentle, or optimistic feeling. Impressionist artworks often employed high-key palettes to depict bright outdoor scenes. A low-key drawing, by contrast, relies heavily on dark values and minimal highlights, often creating a moody, mysterious, or dramatic atmosphere. Many film noir compositions and Baroque paintings exhibit low-key value ranges. A mid-key drawing balances both extremes with an abundant presence of midtones, producing a harmonious and naturalistic effect. In all these cases, the artist is intentionally choosing how much of the value scale in art to use and where to focus the tonal emphasis.

An often overlooked but essential aspect of the value scale in art is that it allows artists to study relative contrast—how values relate to one another within a composition. Even if an artwork uses the full range from white to black, the artist must determine whether specific areas should have strong contrasts or gentle shifts. For example, a face in a portrait may have delicate transitions across its rounded surfaces, requiring subtle value differences to avoid harsh edges. Meanwhile, the edges of clothing, hair, or cast shadows might need stronger contrasts to ensure they stand out or define form. Controlling contrast is not only about technical accuracy but also about directing the viewer’s attention. High contrast naturally draws the eye, while low contrast recedes into the background. Thus, the value scale in art is deeply connected to composition and visual hierarchy.

The value scale in art also helps artists understand light behavior, including how different surfaces interact with illumination. Smooth surfaces, like glass or metal, produce sharp, bright highlights and deep shadows, requiring more extreme jumps along the value scale in art. Rough or matte surfaces, like skin or fabric, produce softer transitions and narrower value ranges. By studying the scale, artists learn to see these differences and reproduce them convincingly. Understanding how values shift across different textures is a foundational skill in drawing from observation.

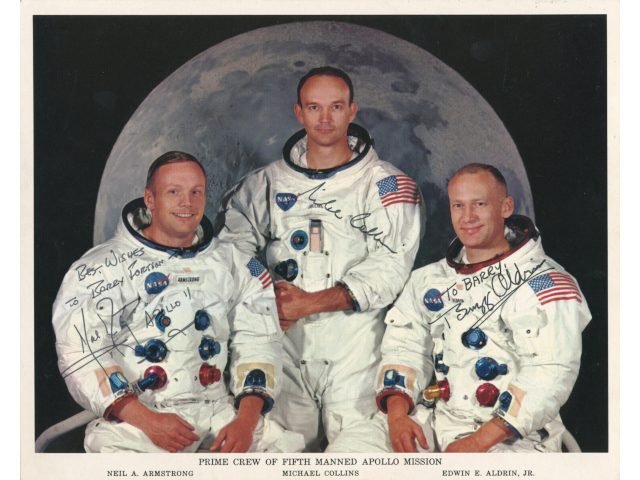

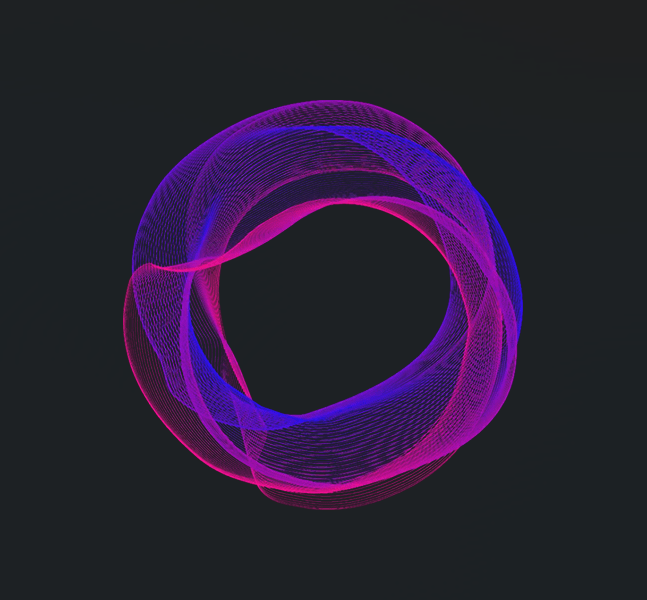

Beyond representing physical form, the value scale in art is a crucial expressive tool. Value carries emotional and symbolic meaning. Dark tones often evoke feelings of mystery, tension, or melancholy, while light tones suggest clarity, purity, or openness. Many artists use the full range of the value scale in art strategically to shape a narrative or emotional experience. For example, an artist might choose to keep the background in darker tones while highlighting a central figure to evoke a sense of isolation, revelation, or importance. Conversely, flattening the value range can create a more graphic, abstract, or stylized effect. Even in non-representational art, value contrast contributes strongly to visual rhythm, balance, and energy.

The range in the value scale in art also influences how artists depict space and atmosphere. Lighter values and lower contrasts often appear to recede into the distance because atmospheric perspective softens distant objects. Darker values and higher contrasts tend to appear closer to the viewer. By manipulating value range intentionally, artists can create illusions of depth without relying on complex line work or color theory. Landscape artists frequently employ value ranges to represent fog, sunlight, dusk, or vast distances.

Although the traditional grayscale value scale in art is the most commonly taught in drawing, understanding value is equally important in color artwork. Every color has an inherent value, and artists who fail to consider this may struggle to maintain coherent lighting. For example, a bright yellow may appear very light in value compared to a deep blue, even if their saturation levels are similar. When artists translate color scenes into grayscale, they often discover surprising value relationships that improve their understanding of composition. Thus, the range in the value scale in art extends beyond black and white drawing and forms the backbone of effective color work.

Developing skill with value range requires deliberate practice. Many drawing students begin with simple exercises such as creating value scale in arts using graphite, charcoal, or ink wash. These exercises teach how to control pressure, blending, layering, and mark-making to produce consistent gradations. The act of manually creating a value scale in art helps train the eye to detect subtle differences in brightness and teaches the hand how to replicate them reliably. More advanced exercises involve applying value ranges to spheres, cubes, and cylinders, which helps artists understand how light interacts with three-dimensional forms. Eventually, artists learn to create full compositions that balance the value scale in art thoughtfully and effectively.

Monitoring the range of values used in a drawing is also essential for maintaining cohesion. Beginners often struggle with “value compression,” a tendency to keep all tones too close together near the lighter or middle part of the scale, resulting in flat and lifeless drawings. Others may use too much contrast without considering the form, producing harsh transitions and unnatural lighting. Understanding the range in the value scale in art helps prevent these issues. With practice, artists begin to use the full range more confidently, gradually learning how to strengthen shadows, brighten highlights, and modulate midtones.

We should also acknowledge that the value scale in art is not merely a static chart—it is a dynamic mental framework. When applied to real-life drawing, the full range does not always appear on every object. For example, a white object in soft light may only contain a small portion of the value scale in art, whereas a black object in dramatic lighting may contain nearly the entire range. The artist must decide whether to depict the values exactly as seen or adjust them for aesthetic, emotional, or compositional reasons. This awareness elevates the value scale in art from a technical diagram to a flexible, interpretive tool in the artist’s creative process.

The range in the value scale in art also communicates narrative. Consider the difference between a drawing of a dimly lit room using a predominantly low-key value range versus a bright outdoor portrait using a high-key range. The low-key drawing may convey secrets, introspection, or tension; the high-key drawing may suggest openness, vibrancy, or peace. Even without color, the manipulation of value range can change the entire story embedded in the artwork. A single figure rendered in stark black-and-white contrast may appear bold, powerful, or isolated, while the same figure rendered in soft greys may appear tender, calm, or contemplative.

Advanced artists also use the value scale in art to control stylistic direction. Hyperrealists often employ a full value range to achieve photographic accuracy, while graphic artists may consciously limit the range to create a bold, stylized appearance. Illustrators, comic artists, and animators use value range to guide visual storytelling and ensure clarity of forms. Painters use it to unify compositions and preserve focus amid complex color schemes. Across all disciplines, the range in the value scale in art remains a central organizing principle that shapes artistic decision-making.

Ultimately, understanding the range in the value scale in art empowers artists with the ability to transform flat surfaces into compelling visual experiences. It teaches them to see in terms of light and shadow, to recognize the subtleties of tonal variation, and to control visual impact with precision. Whether used for realism, abstraction, illustration, or conceptual work, the value scale in art is a universal language of light that connects centuries of artistic tradition with modern creative practices. Its range—from the brightest white to the deepest black—serves as the foundation upon which visual form, mood, contrast, and meaning are built.

In conclusion, the range in the value scale in drawing represents the complete spectrum of tonal values from light to dark. It is not only a physical chart of grayscale steps but also a conceptual framework that enables artists to model forms, create contrast, evoke emotion, and guide composition. Mastering this range is essential for developing strong observational skills and expressive control. Whether an artist uses the full range, a limited range, or a stylized variation, understanding the value scale in art remains fundamental to producing compelling, convincing, and visually articulate artwork. Without command of value range, drawings risk appearing flat or unclear; with it, they come alive with dimensionality, atmosphere, and narrative depth. The value scale in art is the silent architecture behind every powerful piece of art, shaping how viewers perceive light, space, and emotion. Learning to harness its range is one of the most transformative steps in becoming a confident and expressive artist.