The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (commonly abbreviated as PRB) was a group of English painters, poets, and critics, founded in 1848, who sought to reform art by rejecting what they perceived as the mechanical approach of artists who followed the painter Raphael and the later Renaissance tradition. They aimed instead to return to the abundant detail, intense colors, and complex compositions of Italian art before Raphael—especially that of the Italian Quattrocento (the 1400s). The Brotherhood’s very name encapsulates its meaning: Pre-Raphaelite signifies their desire to draw inspiration from the artistic purity, sincerity, and meticulous observation found in works prior to Raphael’s High Renaissance style. The term Brotherhood conveys their vision of themselves not as a loose association, but as a tightly knit, almost secretive fraternity committed to shared ideals in art and literature.

The movement was as much a philosophy as it was an art style. It reflected dissatisfaction with the Royal Academy’s dominance and the rigid conventions of academic art in Victorian England. The PRB felt that art had become formulaic, overly concerned with idealized beauty, and divorced from nature and truth. They wanted to produce work that was fresh, truthful, and deeply meaningful, rooted in both nature’s realism and moral seriousness. For them, returning to “pre-Raphaelite” principles meant restoring honesty and vibrancy to art by combining detailed natural observation with imaginative storytelling.

Historical Context

The PRB’s emergence in 1848 was not a coincidence. This was a year of political upheaval across Europe—the so-called “Year of Revolutions.” Although Britain was not rocked by revolution on the same scale as continental countries, it was a time of deep social, economic, and cultural change. The Industrial Revolution had transformed cities, altered landscapes, and shifted the rhythms of life, creating tensions between tradition and progress. Many artists and intellectuals saw industrialization as eroding the beauty of the natural world and the integrity of human labor.

In the art world, the Royal Academy of Arts—founded in 1768—held near-total authority over what counted as “serious” art. Its president in the mid-19th century, Sir Joshua Reynolds, promoted ideals that stressed classical composition, balanced forms, and generalized beauty. The PRB nicknamed Reynolds “Sir Sloshua” for what they saw as his loose and uninspired approach. They rebelled against these conventions, believing that imitation of the High Renaissance had led to art that was lifeless and mannered.

Simultaneously, there was a Medieval Revival in architecture, literature, and design, fueled partly by the Gothic Revival in church building and partly by the writings of John Ruskin, the influential art critic. Ruskin’s advocacy for truth to nature and his belief in the moral purpose of art resonated strongly with the PRB. This historical climate—industrial discontent, academic stagnation, and medieval romanticism—created fertile ground for their radical yet backward-looking vision.

Founding of the Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in September 1848 in London by seven young men:

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti – poet and painter, often seen as the charismatic heart of the group.

- William Holman Hunt – painter known for his vivid colors and moral seriousness.

- John Everett Millais – the technically gifted painter who later became the most successful commercially.

- James Collinson – painter and devout Catholic who later left the group for religious reasons.

- Frederic George Stephens – painter who eventually abandoned art for art criticism.

- Thomas Woolner – the only sculptor in the group.

- William Michael Rossetti – Dante Gabriel’s brother, who acted as the group’s secretary and chronicler.

The Brotherhood’s meetings took place in Millais’s studio. They even produced a short-lived journal called The Germ, which published poetry, essays, and stories reflecting their ideals. They kept the “PRB” initials semi-secret, signing them on paintings, which intrigued—and sometimes baffled—viewers and critics.

Core Principles

While the PRB never issued a rigid manifesto, their shared beliefs can be summarized in several key principles:

- Truth to Nature – Every detail in a painting should be observed directly from life. This meant painting real plants, landscapes, and models with accuracy, even in historical or biblical scenes.

- Moral Seriousness – Art should be morally and spiritually uplifting, telling stories with moral or symbolic weight.

- Sincerity – Artists should paint what they genuinely felt and saw, not imitate fashionable styles.

- Medievalism and Early Renaissance Influence – Their art drew from medieval subjects, literature, and techniques, inspired by pre-16th-century Italian art.

- Intense Color and Detail – They used luminous colors, often achieved through a technique of painting on a white ground, which made the colors more vibrant.

- Integration of Literature and Art – Many PRB works were inspired by poetry, Shakespeare, the Bible, or medieval romances. Several members were both poets and visual artists.

Artistic Style and Technique

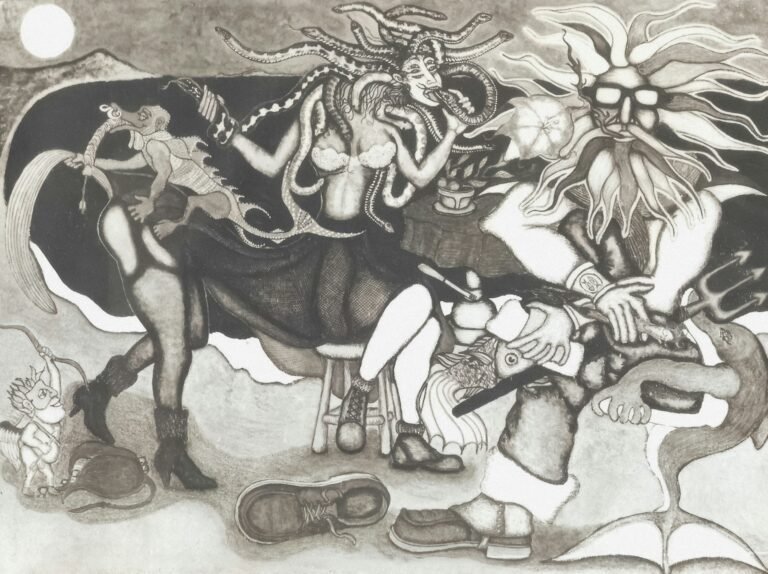

The PRB’s style was immediately recognizable. Their paintings combined microscopic attention to natural detail with carefully staged compositions. They often worked outdoors (a practice called “plein air” painting) to capture the exact lighting and colors of a scene. They rejected the dark, varnished look typical of academic art, preferring bright, jewel-like tones.

Their technique involved applying thin layers of paint over a white ground, which made the pigments glow with an inner luminosity. Figures were rendered with sharp clarity, and backgrounds often contained intricate symbolic details. This combination of realism and symbolism was one of their signatures.

Subjects were often drawn from religious themes, medieval legends, and literary sources. For example, Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World is a deeply symbolic depiction of Christ knocking at a closed door, symbolizing the human soul. Millais’s Ophelia, based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, shows the tragic heroine floating in a river surrounded by botanically accurate flowers. Rossetti often painted sensual, idealized women inspired by Dante, Arthurian legend, or his own poetry.

Reception and Controversy

When the PRB first exhibited their works at the Royal Academy in 1849–1850, the reaction was mixed and often hostile. Critics accused them of ugliness, awkwardness, and a lack of respect for tradition. Charles Dickens famously ridiculed Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents (1849–50), calling it a portrayal of “a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering red-headed boy in a bed-gown.”

However, the PRB soon gained an important champion: John Ruskin. In 1851, Ruskin wrote letters to The Times defending them, praising their commitment to truth to nature and sincerity. His support gave them credibility and helped them weather public criticism.

Evolution and Expansion

The original Brotherhood formally lasted only a few years. By 1853, members had drifted apart in style and focus. Millais moved towards a more conventional and commercially successful portrait style. Hunt remained committed to PRB ideals, traveling to the Holy Land to paint biblical scenes with geographical authenticity. Rossetti increasingly focused on sensual, dreamlike images, moving away from strict naturalism.

Yet the PRB’s influence expanded through associates and followers, sometimes referred to as the second generation of Pre-Raphaelites. This included figures like Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, and Ford Madox Brown, who brought a more decorative and romantic approach, paving the way for the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Links with Literature

From the beginning, the PRB was deeply intertwined with literature. Rossetti wrote poetry alongside painting, often exploring the same themes in both. William Michael Rossetti, the group’s chronicler, was also a poet and critic. Their magazine The Germ blended visual and literary art.

They drew on medieval poetry, Shakespeare, Keats, and Tennyson for subject matter. For example, Rossetti’s paintings of Dante’s La Vita Nuova and his sonnets on his artworks (so-called “double works”) show how they saw painting and poetry as inseparable. This cross-pollination made the PRB a rare movement that equally valued visual and literary creation.

Symbolism and Themes

A distinctive feature of PRB art was its use of symbolism—objects in a painting often carried moral or spiritual meaning. In Millais’s Ophelia, every flower corresponds to a plant mentioned in Shakespeare’s play, while in Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience, the littered music sheets and abandoned embroidery speak volumes about the woman’s moral situation.

Common themes included:

- Religious devotion (Hunt’s The Light of the World)

- Tragic love (Millais’s Mariana, Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix)

- Medieval romance (Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel)

- Nature’s truth and beauty

- Moral redemption or downfall

Impact on Victorian Culture

The PRB left a significant mark on Victorian culture beyond painting. Their emphasis on hand craftsmanship and medieval aesthetics influenced architecture, book design, and decorative arts. Through their association with William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, they helped inspire a reaction against industrial mass production in favor of handmade beauty.

Their literary connections also shaped Victorian poetry, contributing to the so-called Pre-Raphaelite Poets, whose works were characterized by sensual imagery, medievalism, and emotional intensity. This influenced later writers like Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement.

Criticism and Limitations

Not all was praise. Some critics found the PRB overly sentimental or self-indulgent. Their medievalism could be seen as escapist, ignoring the pressing social realities of industrial Britain. While they claimed devotion to truth to nature, they often idealized their female subjects, creating a kind of archetypal “Pre-Raphaelite beauty” with long necks, flowing hair, and languid expressions—an image that could be as stylized as the art they rejected.

There were also tensions within the group. Millais’s turn towards a more mainstream style disappointed Hunt and others. Rossetti’s increasingly sensual imagery led some to question whether the moral seriousness of the early PRB had been abandoned.

Legacy

Despite its short lifespan as a formal brotherhood, the Pre-Raphaelite movement had a lasting legacy. It influenced:

- Visual art – inspiring Symbolism and the Aesthetic Movement.

- Literature – through the Pre-Raphaelite poets and their successors.

- Design – via the Arts and Crafts Movement.

- Popular culture – The Pre-Raphaelite look has been revived in fashion, photography, and film.

Today, PRB works are celebrated for their beauty, craftsmanship, and emotional power. Major collections, such as those in Tate Britain and the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, continue to draw visitors. Modern audiences often appreciate the PRB’s combination of natural realism and poetic symbolism in ways their Victorian critics did not.

Conclusion

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was more than just a group of rebellious young artists in 1848—it was a conscious challenge to the conventions of art, a blending of realism and romanticism, and a vision of artistic sincerity that continues to resonate. Their meaning lies in their rejection of academic complacency and their passionate return to a perceived purity of art before Raphael. While their unity as a brotherhood was brief, their impact was enduring, influencing visual art, literature, and design for decades.

Ultimately, the PRB’s legacy is a reminder that art movements are not always about inventing something entirely new; sometimes they are about rediscovering something old—and, in doing so, making it new again.