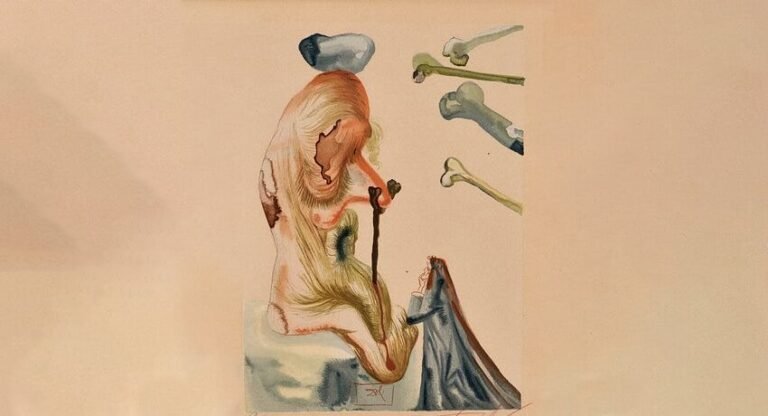

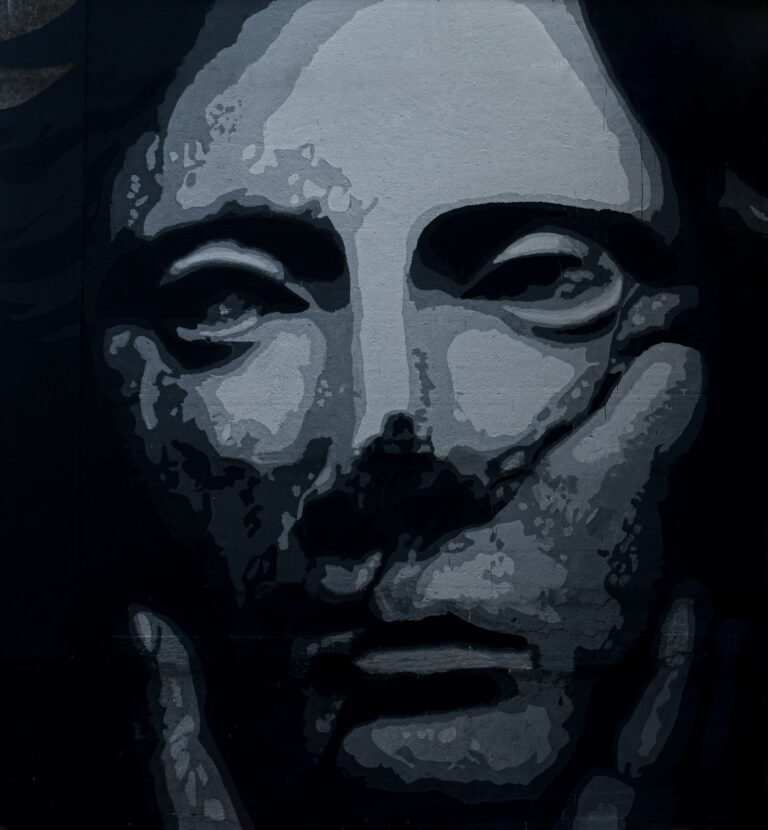

The Son of Man painting, painted by Belgian surrealist René Magritte in 1964, is one of the most enigmatic and widely recognized works of 20th-century art, inviting a multitude of interpretations due to its minimalist composition and surrealist underpinnings. The painting depicts a man in a suit and bowler hat, standing against a neutral background with a sea and cloudy sky, his face obscured by a green apple floating in front of it. This deceptively simple image encapsulates Magritte’s fascination with the tension between visibility and concealment, reality and illusion, and the interplay of identity and anonymity, while also engaging with broader philosophical, psychological, and cultural themes. Below, I explore the multifaceted meanings behind The Son of Man painting, delving into its surrealist context, symbolic elements, philosophical implications, and cultural resonance, while considering Magritte’s own statements and the broader artistic and historical framework in which the painting was created.

At its core, The Son of Man painting is a quintessential surrealist work, reflecting the movement’s aim to probe the unconscious, challenge conventional perceptions, and reveal the strangeness beneath everyday reality. Magritte, a key figure in surrealism, was less interested in the dreamlike automatism of contemporaries like Salvador Dalí and more focused on disrupting the viewer’s expectations through familiar objects placed in unfamiliar contexts. The apple covering the man’s face is a prime example of this technique, creating a visual paradox that invites scrutiny. In his own words, Magritte stated, “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.” This philosophy is central to the painting: the apple conceals the man’s face, frustrating the viewer’s desire to see his identity, and thus forces a confrontation with the act of looking itself. The obscured face suggests that what we perceive is never the full truth, aligning with surrealism’s rejection of straightforward representation in favor of mystery and ambiguity.

The title, The Son of Man painting, adds a layer of complexity, evoking religious and existential connotations. The phrase is often associated with Christian theology, particularly referencing Jesus Christ as the “Son of Man” in the New Testament, a figure embodying both divine and human nature. Magritte, however, was not overtly religious, and his use of the title is likely ironic or subversive, a hallmark of his approach to destabilizing expectations. The apple, a potent symbol in Western culture, reinforces this reading. It recalls the biblical story of Adam and Eve, where the apple represents knowledge, temptation, and the fall from innocence. By placing the apple over the man’s face, Magritte might be suggesting that knowledge (or the pursuit of it) obscures self-understanding, or that humanity’s fall into self-awareness creates a barrier to authentic identity. Alternatively, the apple could symbolize the mundane intruding upon the sacred, reducing the lofty “Son of Man” to a faceless everyman, trapped in the banality of modern life. This interplay of sacred and profane underscores Magritte’s knack for blending high and low, serious and absurd.

The man’s attire—a formal suit and bowler hat—further grounds the painting in the mundane, anchoring its surreal elements in a recognizable reality. The bowler hat, a recurring motif in Magritte’s work (seen in paintings like Golconda and The Man in the Bowler Hat), evokes the archetypal bourgeois figure of mid-20th-century Europe, a symbol of conformity and anonymity. This choice situates the painting within a critique of modern society, where individuality is often subsumed by societal roles and expectations. The facelessness of the man, obscured by the apple, amplifies this idea: he is not an individual but a type, a stand-in for humanity itself. This anonymity resonates with existentialist themes prevalent in the post-World War II era, when thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus grappled with questions of meaning, identity, and the human condition in a world marked by absurdity and alienation. The Son of Man painting can thus be seen as a visual meditation on the loss of self in a mechanized, conformist society, where external symbols (like the apple or the suit) overshadow inner identity.

The apple itself is a rich symbol, open to multiple interpretations beyond its biblical associations. In art history, apples often signify knowledge, desire, or mortality, and Magritte’s use of the fruit taps into these traditions while subverting them. By floating inexplicably in front of the man’s face, the apple defies logic, creating a surreal disjunction that challenges the viewer to question the nature of reality. Is the apple a physical object, a hallucination, or a metaphor? Its placement suggests an obstruction, preventing both the man and the viewer from achieving full clarity. This aligns with Magritte’s broader exploration of perception, as seen in works like The Treachery of Images, where he famously declared, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”), reminding viewers that representations are not reality. In The Son of Man painting, the apple serves a similar function, acting as a barrier between the viewer and the “truth” of the man’s identity, prompting reflection on the limits of perception and the unreliability of visual information.

The composition of the painting reinforces its themes of concealment and revelation. The man’s eyes are partially visible behind the apple, tantalizingly close yet ultimately inaccessible, which heightens the viewer’s frustration and curiosity. This partial visibility is a deliberate choice, as Magritte often played with the idea of “showing and hiding” simultaneously. The background—split between a calm sea and a cloudy sky—adds to the painting’s enigmatic quality. The sea, often a symbol of the subconscious or the infinite, contrasts with the structured formality of the man’s attire, suggesting a tension between the rational and the irrational. The clouds, another recurring motif in Magritte’s work, evoke transience and ambiguity, further destabilizing the viewer’s sense of certainty. Together, these elements create a visual field that is both familiar and alien, inviting viewers to question the stability of the world they inhabit.

Philosophically, The Son of Man painting engages with questions of identity and selfhood, themes that resonate with both existentialist and psychoanalytic frameworks. From an existentialist perspective, the painting reflects the human struggle to define oneself in a world devoid of inherent meaning. The obscured face suggests that identity is not fixed or knowable but is instead fragmented, hidden behind external symbols or societal roles. Psychoanalytically, the apple could be seen as a manifestation of repression, blocking access to the true self or the unconscious. Sigmund Freud’s theories, influential in surrealist circles, emphasized the hidden forces shaping human behavior, and Magritte’s painting seems to visualize this idea by placing a barrier (the apple) between the conscious self (the man’s outward appearance) and the inner self (his face). The tension between these layers of meaning invites viewers to confront their own assumptions about who they are and how they are perceived.

Culturally, The Son of Man painting reflects the anxieties of its time. Painted in 1964, it emerged in the context of the Cold War, a period marked by existential dread, technological advancement, and the rise of mass culture. The faceless man in a suit could be read as a critique of the dehumanizing effects of bureaucracy, consumerism, and conformity, themes also explored by artists like Andy Warhol and writers like George Orwell. The painting’s minimalist aesthetic and accessible imagery also anticipate the rise of pop art, which blurred the lines between high art and popular culture. Indeed, The Son of Man painting has become a cultural icon, reproduced in everything from advertisements to film references (notably in The Thomas Crown Affair), underscoring its universal appeal and open-ended meaning. This widespread recognition speaks to the painting’s ability to resonate across contexts, tapping into timeless questions about identity and perception.

Magritte’s own commentary on the painting offers some insight, though he was notoriously reticent about definitive interpretations. He described The Son of Man painting as a self-portrait, albeit one that conceals more than it reveals. This aligns with his broader practice of using self-portraiture to explore universal themes rather than personal biography. In a letter to a friend, Magritte noted that the painting was inspired by a moment of spontaneous vision, where he imagined a man’s face obscured by an apple, suggesting that the image emerged from an intuitive, almost subconscious process. This origin story underscores the surrealist emphasis on the irrational and the unexpected, but it also leaves room for viewers to project their own meanings onto the work. Magritte’s reluctance to pin down a single interpretation reflects his belief that art should provoke questions rather than provide answers, a stance that makes The Son of Man painting endlessly interpretable.

The painting’s formal qualities also contribute to its meaning. Magritte’s style is characterized by a crisp, almost photographic realism, which contrasts sharply with the surreal content of his images. This hyper-realistic rendering of the man, apple, and background creates a sense of uncanny familiarity, making the strange seem almost plausible. The muted color palette—dominated by the gray of the suit, the green of the apple, and the subdued tones of the sea and sky—enhances the painting’s dreamlike quality, while the clean lines and balanced composition lend it a sense of order that belies its disruptive intent. This tension between form and content is central to Magritte’s practice, as he uses the language of realism to undermine the viewer’s trust in reality itself.

In a broader art-historical context, The Son of Man painting can be seen as part of a lineage of works that explore the human face as a site of meaning and mystery. From the veiled figures of Renaissance portraiture to the fragmented faces of Picasso’s cubism, artists have long used the face to probe questions of identity and representation. Magritte’s contribution is to literalize this concealment, making the obstruction (the apple) a central element of the composition. The painting also resonates with contemporary works like Francis Bacon’s distorted portraits, which similarly destabilize the human form, though Magritte’s approach is more restrained and cerebral. By placing The Son of Man painting within this tradition, we can see it as both a continuation of and a departure from earlier explorations of the self, uniquely suited to the existential and cultural concerns of the 20th century.

Ultimately, The Son of Man painting resists a singular interpretation, functioning as a mirror for the viewer’s own questions and anxieties. Its power lies in its ability to provoke without resolving, to invite scrutiny while withholding answers. Whether read as a meditation on identity, a critique of modernity, a surrealist riddle, or a philosophical inquiry into perception, the painting remains a potent symbol of the human condition. Its iconic status is a testament to its universal resonance, as it continues to captivate audiences with its blend of mystery, humor, and profundity. By concealing the man’s face behind an apple, Magritte reminds us that the search for meaning is both a universal impulse and an unattainable goal, leaving us to grapple with the enigma of ourselves.