Art has always been a powerful means of human expression, serving not only as a reflection of society but also as an instrument of change. Among the many forms and functions of art, protest art stands out as one of the most socially and politically charged cultural phenomena. Protest art may be defined as art that challenges, criticizes, or resists established power structures, injustices, inequalities, or oppressive systems. Unlike art created purely for aesthetic appreciation, protest art is driven by the intention to provoke awareness, trigger conversations, disrupt complacency, and inspire collective action. Its power lies not only in its imagery, symbolism, or style, but also in its function as a form of dissent. In every era and geographical context, people have turned to creative expression to convey grievances and unite against exploitation, and this continuity makes protest art a universal language of resistance and hope.

Protest art, by nature, confronts dominant ideologies and questions the values imposed by political, economic, and social authorities. Whether it takes the form of murals, posters, graffiti, music, performance art, digital media, or literature, protest art directly interacts with public consciousness. Its imagery often taps into the emotions of viewers, enabling messages of resistance to reach wider audiences beyond political speeches or academic texts. The effectiveness of protest art stems from its accessibility: it communicates to people irrespective of class, literacy level, or language. A striking image, a symbolic gesture, or a provocative installation can resonate more deeply than long manifestos or complex debates. This democratizing characteristic makes protest art a powerful companion to political movements and social struggles.

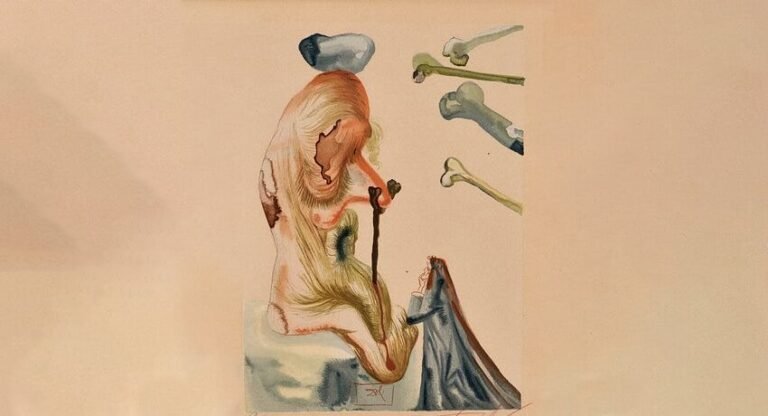

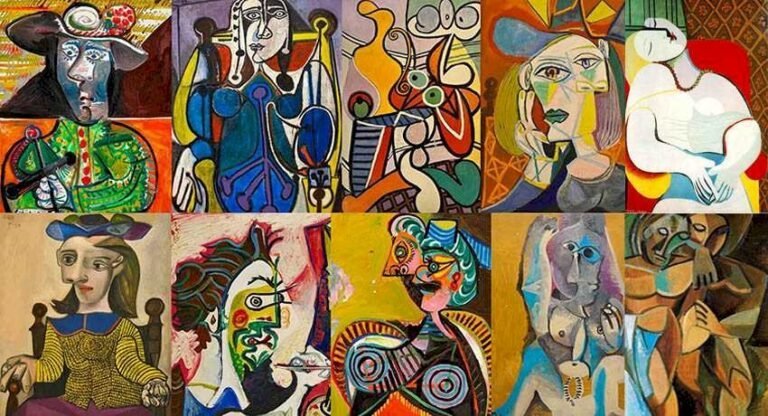

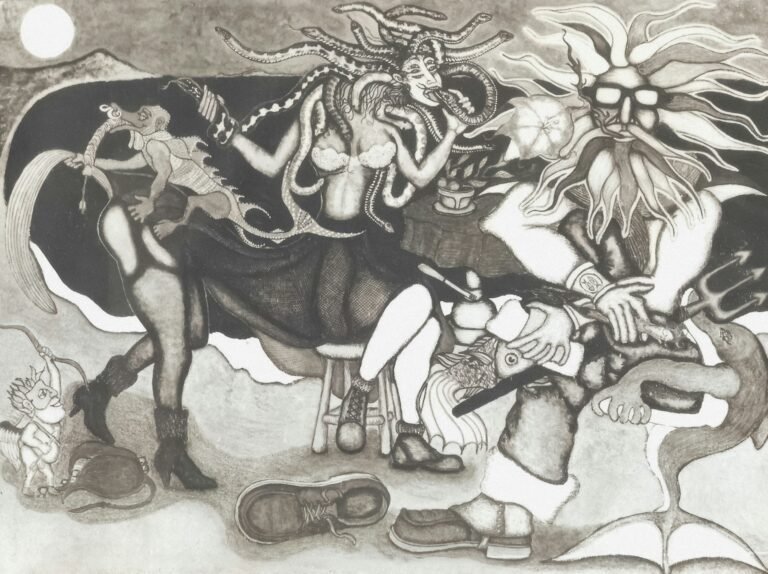

Historically, protest art has emerged in response to oppression, colonialism, war, censorship, racism, patriarchy, class exploitation, environmental destruction, and state violence. For instance, Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 protested the cruelty of war, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica condemned fascist bombing in Spain, and Käthe Kollwitz depicted the suffering of the working class in early 20th-century Europe. In the United States, protest art fueled the Civil Rights Movement through posters and songs, and the anti-Vietnam War movement used photography, painting, and performance to criticize militarism. More recently, the Black Lives Matter movement, climate activism, feminist campaigns such as #MeToo, and protests against authoritarian regimes across the world have all employed powerful visual and creative strategies to amplify their voices. These examples demonstrate that protest art is not limited to a particular form or era, but constantly evolves alongside global sociopolitical issues.

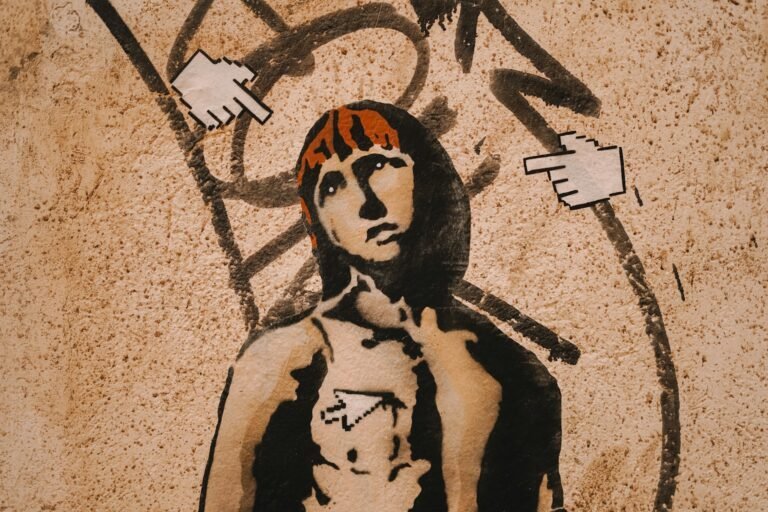

From a broader perspective, protest art is not merely an artistic category but a mode of social engagement. It challenges traditional notions of what art should be and who should create it. By stepping outside museums and galleries, protest art occupies public spaces where people live, work, and struggle. Graffiti on city walls, banners on streets, handmade posters in rallies, and digital artworks circulating online are all examples of protest art that bypass commercial art markets and elitist institutions. This shift undermines the long-held belief that art must be preserved in controlled environments or created by professionally trained artists. Protest art empowers ordinary individuals to participate creatively in political discourse. It demonstrates that anyone with imagination and conviction can contribute to resistance through artistic expression.

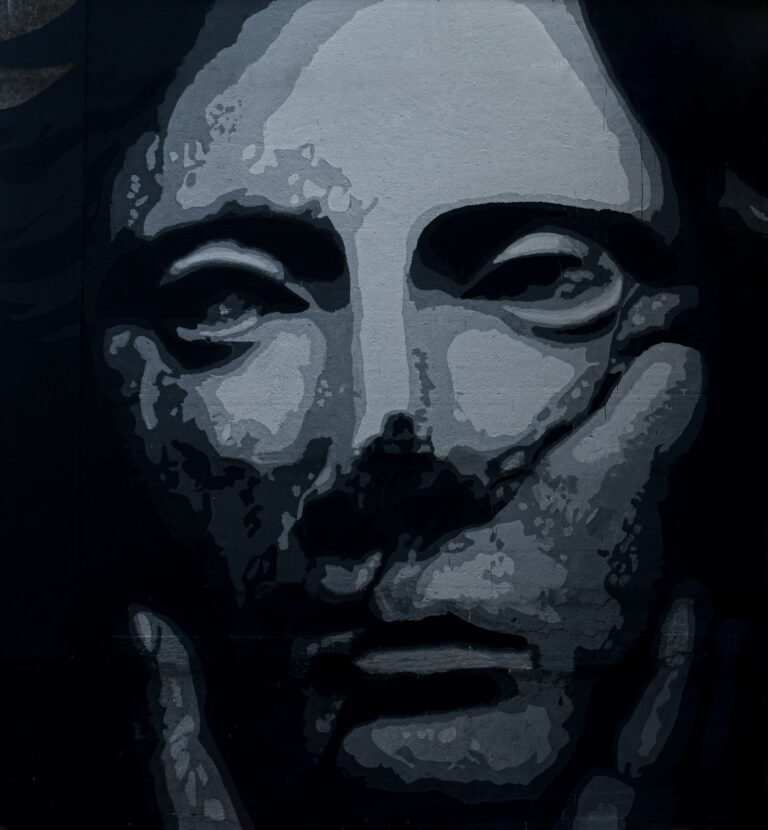

Equally significant is the perspective that protest art communicates collective identity. In movements of resistance, art strengthens unity by shaping a shared visual and cultural vocabulary. Symbols such as raised fists, broken chains, peace signs, or stylized portraits of revolutionaries (like Che Guevara) have become iconic markers of collective struggle. These images transcend borders and serve as reminders of solidarity across nations and communities. Protest art therefore not only resists oppressive systems but also nurtures a sense of connection among diverse groups fighting for justice. Through this shared identity, people gain motivation and inspiration to continue their struggle even in the face of adversity.

Yet, protest art does more than unify; it also disrupts and challenges power. By giving voice to the oppressed, it forces those in authority to reckon with criticism they would rather silence. Many governments and institutions are uncomfortable with protest art precisely because it mobilizes public opinion. Throughout history, authoritarian regimes have censored or destroyed works of dissent, arrested artists, and restricted public art production. This reaction reveals the potent influence of protest art: if it were harmless, there would be no need to suppress it. The attempt to control artistic expression demonstrates that protest art poses a threat to hegemonic narratives and exposes systems of inequality and corruption. The power dynamics between protest art and censorship highlight its function as a form of resistance that challenges both cultural and political dominance.

Furthermore, protest art is not confined to political matters alone; it also interrogates social norms, ethical values, and cultural assumptions. Feminist art, for example, critiques patriarchal structures, gender stereotypes, and se xual violence. Artists like Judy Chicago, Guerrilla Girls, and Frida Kahlo used their work to question male-dominated art institutions and the marginalization of women’s experiences. Similarly, LGBTQ+ protest artists challenge heteronormativity and discrimination, using creative platforms to assert identity and dignity. Environmental activists use photography, installations, and digital media to warn about climate crises, deforestation, and extinction. Indigenous artists protest cultural erosion, land theft, and colonial exploitation through traditional as well as contemporary forms. Thus, protest art engages with the full spectrum of human struggle, not only against political institutions but also against social prejudices, cultural erasure, and environmental degradation.

A crucial perspective on protest art is its emotional and psychological impact. Art that expresses suffering, injustice, or oppression often evokes empathy and moral reflection in audiences. When viewers encounter disturbing images of violence, displacement, hunger, or discrimination, they are compelled to confront realities they may otherwise ignore. Protest art therefore acts as a mirror that reflects uncomfortable truths, persuading individuals to reconsider their beliefs and responsibilities. At the same time, protest art can empower victims by allowing them to narrate their trauma in their own voices. In this sense, protest art functions as a therapeutic tool and a means of reclaiming identity. For communities whose histories have been silenced by dominant powers, protest art becomes an archive of resistance, recording memories that might otherwise be erased.

Another important perspective concerns the transformation of protest art in the digital age. With the rise of social media, digital illustration, and online activism, protest art has reached new dimensions. Messages can now circulate across the globe in seconds, allowing visual narratives to influence international opinion and strengthen transnational solidarity. Memes, viral posters, digital caricatures, hashtags paired with artwork, and livestreamed performances have become new forms of political engagement. Digital protest art democratizes creation even further, enabling participation without physical presence. However, it also introduces challenges, such as misinformation, superficial activism, and appropriation of protests for commercial purposes. While online protest art can mobilize large audiences, its rapid spread can dilute meaning when individuals share images without understanding the movement behind them. Thus, the digital perspective highlights both the strengths and the risks of contemporary protest art.

Protest art also invites debate about whether it should be valued primarily for its political effect or its artistic quality. Some critics argue that art loses aesthetic value when it becomes explicitly political. They view protest art as propaganda or emotional manipulation rather than creative expression. However, many artists and scholars reject this binary view, arguing that art is inherently political because it emerges from lived human experiences shaped by power structures. Low-income households, marginalized communities, and oppressed groups cannot ignore the political nature of their reality; therefore, their art cannot be detached from their struggles. From this standpoint, protest art does not sacrifice aesthetic value—it transforms aesthetics into a tool of empowerment.

Moreover, protest art challenges elitism in the art world. Traditional art institutions often prioritize commercial value, prestige, and stylistic innovation over social relevance. Protest art disrupts this hierarchy by prioritizing message over market value. Murals painted on community walls or posters handed out during protests are not meant to be sold in galleries; they exist as public property. Their belonging to the collective rather than to the elite redefines the purpose of art in society. This redefinition fuels important discussions about accessibility, ownership, and the relationship between artists and their audiences. It suggests that art should not be reserved for affluent collectors or exclusive museums but should serve as a catalyst for dialogue, empowerment, and change.

In addition, the perspective of protest art must include its potential limitations. Not all protest artworks create tangible political outcomes. Some may be praised on social media but fail to influence policy or mobilize grassroots action. Artistic protests can be co-opted by corporations, governments, or mainstream culture, stripping them of radical intent and transforming them into fashionable commodities. For example, revolutionary symbols have been commercially commodified, such as Che Guevara’s iconic portrait printed on consumer goods without commitment to revolutionary ideology. Similarly, political slogans used in marketing campaigns may undermine genuine activism. These contradictions illustrate the tension between protest art as resistance and protest art as marketable culture. Therefore, to fully understand protest art, one must recognize both its transformative potential and its vulnerability to commodification.

Nonetheless, despite these contradictions, protest art continues to inspire social consciousness. Even when commodified or misused, its imagery retains the capacity to remind viewers of struggles and the existence of injustice. Moreover, protest art often sparks conversations that lead to deeper engagement. When a mural provokes debate, or a poster goes viral, even critics contribute to the visibility of the cause. Engagement, whether positive or negative, ensures that the issues remain alive in public discourse. For this reason, protest art cannot be measured solely by immediate political impact; its influence unfolds gradually through education, awareness, and cultural memory.

Ultimately, the perspective surrounding protest art connects aesthetics with ethics, creativity with activism, and emotion with intellect. Protest art urges individuals to question their role in perpetuating or challenging systems of inequality. It shows that art is not neutral; it either reinforces dominant ideologies or resists them. By revealing uncomfortable truths and amplifying hidden voices, protest art invites audiences to reflect on their own values and responsibilities. Its purpose is not only to protest externally against governments and institutions, but also to provoke internal transformation. Protest art calls upon each person to recognize their agency in shaping society.

Conclusion

Protest art is more than a creative expression—it is a transformative force that communicates resistance, shapes collective identity, and challenges oppressive systems. Through murals, posters, performances, digital images, literature, and songs, it reaches diverse audiences and inspires social consciousness. From historical resistance movements to digital activism, protest art continues to evolve as a global language of dissent. Its power lies in its accessibility, emotional impact, and ability to disrupt dominant narratives. Although it faces challenges such as censorship, commodification, and superficial engagement, protest art remains a vital instrument for social change. By confronting injustice and empowering marginalized voices, protest art not only gives shape to resistance but also reminds humanity of its shared responsibility to seek justice, freedom, and equality. In essence, protest art is both a reflection of human struggle and a beacon guiding societies toward transformation.