Modern protest art is one of the most dynamic and powerful artistic movements of the contemporary world. Unlike traditional art, which often focuses on beauty, spirituality, or personal expression, modern protest art is deliberately confrontational. It seeks to expose injustice, provoke debate, mobilize communities, and catalyze social change. Its foundation lies in transforming visual communication into political resistance—turning images, performances, and public interventions into tools capable of challenging governments, oppressive systems, and cultural norms. From street murals and protest posters to digital memes and performance art, the modern protest art movement reflects ongoing struggles across the globe. Its history is rooted in colonial resistance, civil rights battles, feminist struggles, anti-war movements, and more recently, global demands for racial justice, climate action, indigenous rights, and democratic fre edom.

Origins of Protest Art: Seeds of Modern Expression

The roots of modern protest art stretch back hundreds of years, but its emergence as a formal and recognized cultural force began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Early forms of what we now call protest art can be seen in satirical prints that criticized governments and aristocracies. For example, Honoré Daumier’s lithographs in France used humor and caricature to ridicule kings and corrupt politicians, pushing the boundaries of fre e speech. However, the political and social revolutions of the early 1900s helped protest art evolve from critique into mobilization.

The Mexican Muralist Movement, led by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, marked a major turning point. After the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), these artists painted large public murals depicting class struggle, the exploitation of workers, Indigenous heritage, and anti-imperialist messages. They believed that art should belong to ordinary people rather than exist in elite galleries. Their philosophy of “art for the masses” became a cornerstone of modern protest art culture.

During the same period, propaganda posters emerged in Russia, China, and many parts of Europe. While these posters were sometimes government-led, they demonstrated how visual art could influence public opinion on a mass scale. Revolutionary art became both a weapon against oppression and a tool used by states to consolidate power. This duality—art as fre edom and art as control—remains a defining tension within protest art history.

Protest Art in the Mid-20th Century: Civil Rights, Anti-War Movements, and Counterculture

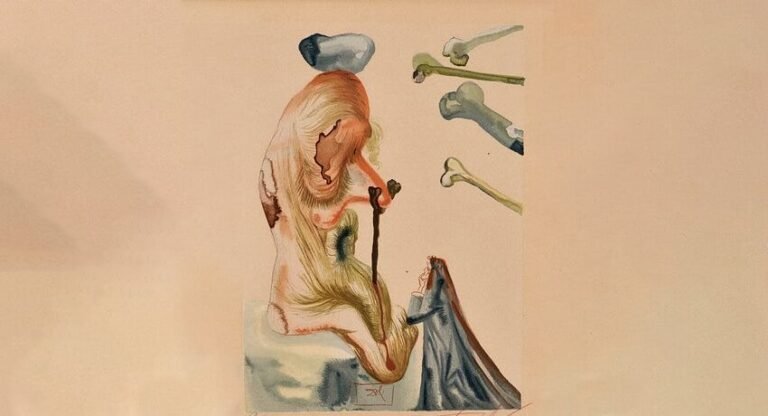

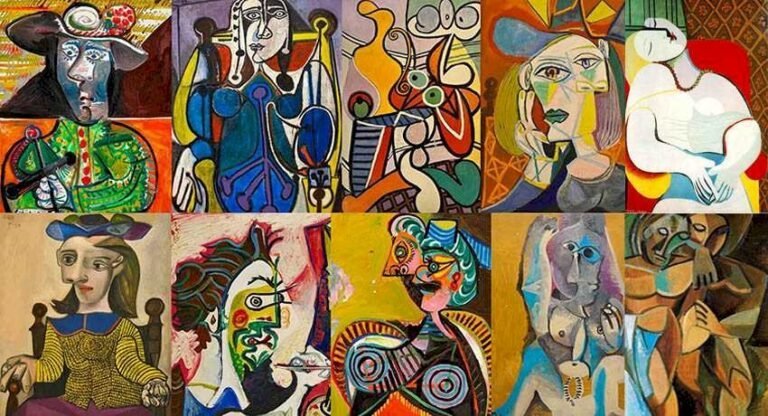

The twentieth century saw a boom in protest art, particularly in response to war, racism, and economic inequality. The horrors of World War II inspired artists to depict human suffering and question authoritarianism. Pablo Picasso’s famous painting Guernica (1937), created in response to the bombing of a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War, is often considered one of the most iconic anti-war artworks in history. Its abstract, chaotic depiction of civilian anguish helped set a symbolic and emotional tone for future anti-war art campaigns.

The 1950s and 1960s gave rise to powerful protest art across the world, particularly with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Posters demanding racial equality, photographs documenting police brutality, and protest songs became essential tools for activists. Artists such as Emory Douglas, who worked with the Black Panther Party, used bold illustrations to portray African Americans as strong, revolutionary figures confronting systemic racism. His work challenged mainstream media depictions and empowered Black communities, demonstrating how protest art could reclaim identity and self-representation.

The Vietnam War catalyzed another wave of protest art. Anti-war posters, music, photography, and performance art reflected growing opposition among young people, students, and counterculture groups. The peace symbol, originally designed for the British nuclear disarmament movement in 1958, became universal. Protest art in this period emphasized nonviolent resistance, youth rebellion, and skepticism toward government authority. Public art demonstrations, such as the Yippie performance protests, blurred the lines between theater and activism. This was the era when art ceased to be primarily symbolic—it became participatory, inclusive, and embodied through public performance.

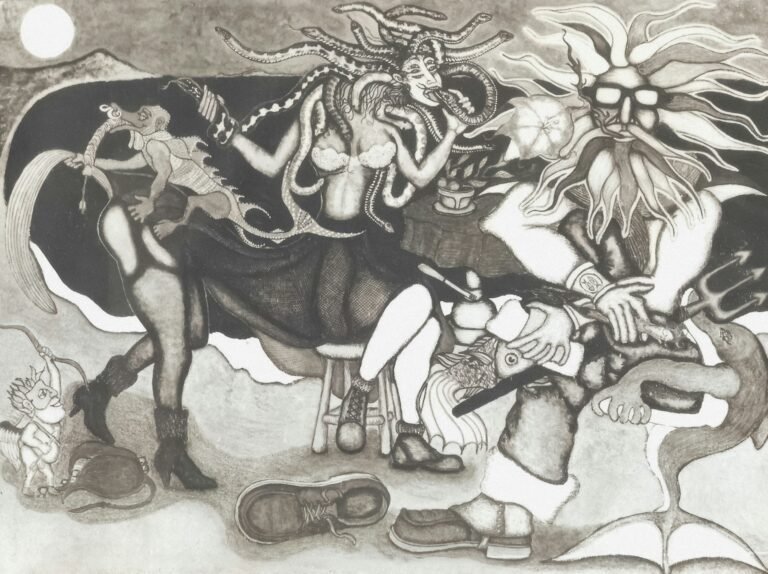

Feminist and Queer Protest Art: Challenging Patriarchy and Redefining Identity

As social activism expanded in the 1970s and 1980s, feminist and queer protest art emerged as significant cultural movements. Artists began challenging patriarchal structures, demands for bodily autonomy, and the cultural invisibility of marginalized genders and sexualities. One of the most notable feminist protest art groups was the Guerrilla Girls, who used humor, statistics, and bold graphic posters to expose sexism and racism in the art world. Wearing gorilla masks to hide their identities, they highlighted how major museums and galleries historically excluded women and minority artists. Their activism demonstrated how protest art could critique not only politics but the art world itself.

Similarly, LGBTQ+ protest art emerged as a response to discrimination and the AIDS crisis. Activist art collectives like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) used provocative graphics, slogans, and street interventions to demand funding, medical research, and social acceptance. The “Silence = Death” poster, featuring a simple pink triangle, became one of the most powerful visual symbols of queer resistance. LGBTQ+ protest art broke cultural silence surrounding sexuality and illness, transforming shame and marginalization into public defiance.

Street Art Revolution: Graffiti as Political Resistance

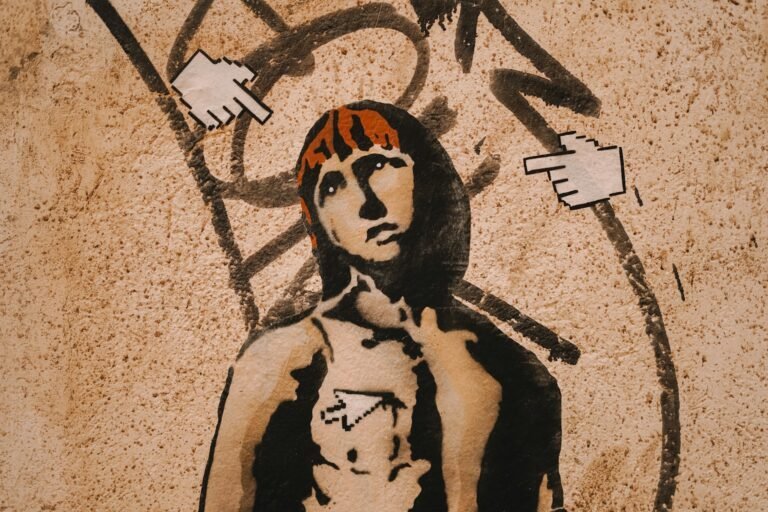

Modern protest art underwent another transformation with the rise of street art and graffiti in the late twentieth century. Urban environments became canvases for dissent. Graffiti, once dismissed as vandalism, evolved into a global art form associated with fre edom, rebellion, and youth identity. Street artists used walls to voice frustration with police violence, gentrification, corruption, and economic inequality. The anonymity of graffiti allowed marginalized voices to speak without fear of punishment.

In this period, artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat used street imagery to criticize capitalism, consumerism, racism, and the AIDS epidemic. Later, the anonymous artist Banksy popularized politically charged stencil art. Banksy’s works critiqued war, surveillance, corporate exploitation, and refugee crises, showing how humor and simplicity could challenge global power structures. Street art also became closely linked with revolutions. During the Arab Spring (2010–2012), murals across Cairo and Tunis memorialized martyrs, condemned dictators, and strengthened collective identity. The street became a battlefield of ideas, where walls carried the voices of the oppressed.

Digital Protest Art: Memes, Hashtags, and Virtual Resistance

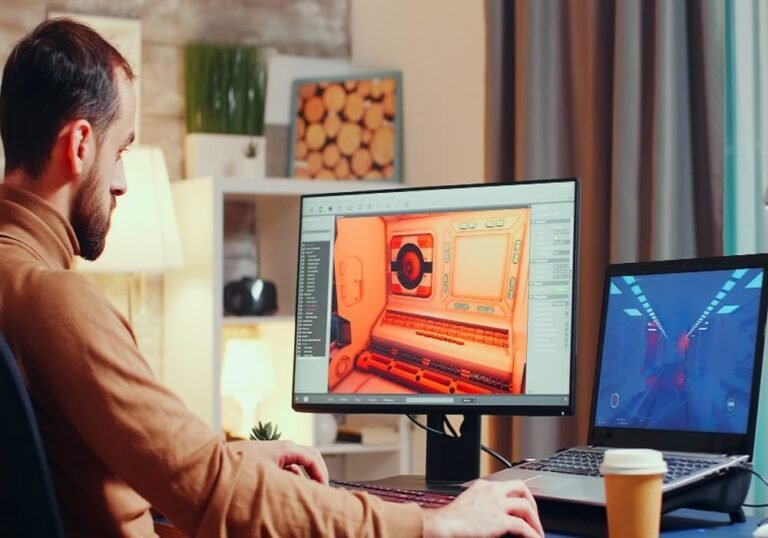

In the twenty-first century, protest art shifted dramatically due to globalization and digital technology. Social media platforms—Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Facebook, and others—turned everyday citizens into artists and activists. Protest art no longer required museums, street walls, or political organizations. Anyone with a smartphone could create and share political images that spread globally within minutes. This democratization of artistic expression allowed marginalized communities to voice their struggles without institutional mediation.

Digital protest art gained enormous visibility through movements such as Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Occupy Wall Street, environmental justice campaigns, and Indigenous land rights activism. Viral posters, infographics, illustrations, and memes became critical tools for mobilizing communities and documenting crises. During the 2020 George Floyd protests, digital artworks portraying victims of police brutality circulated widely, transforming individual tragedies into collective demands for justice. Similarly, pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong created anonymous manga-style drawings to maintain solidarity and protect their identities from state surveillance.

Memes became particularly influential as forms of protest art. While humorous, memes simplify political critique into shareable and relatable messages. They challenge authority through satire, making complex social issues accessible to younger generations. Digital protest art also challenges mainstream media; marginalized groups no longer depend on traditional journalism to document injustice—they produce their own narratives, preserving cultural memory through images.

Cultural Dimensions of Modern Protest Art

Modern protest art reflects not only political struggles but also cultural context. It expresses collective identity, memory, spirituality, gender experience, and cultural pride. For Indigenous communities, protest art often reconnects with ancestral symbols, craft practices, and languages suppressed by colonialism. For example, Indigenous Australian art frequently incorporates Dreamtime motifs into murals demanding land rights and environmental protection.

In countries facing censorship, protest art often uses metaphor, humor, and coded imagery to bypass state control. Chinese and Russian activists sometimes rely on symbolic animals, colors, or wordplay to critique authoritarianism without explicit statements. In contrast, democratic societies often use protest art to question capitalism, corporate power, and social inequality.

Music, dance, and performance art also hold cultural significance. Hip hop, born as a protest culture in African American neighborhoods, remains one of the most influential global art forms for articulating justice, identity, and resistance. Similarly, Indigenous powwow dances, Afro-Brazilian Capoeira, and South Asian street theater reflect cultural resilience through artistic practice.

The Role of Aesthetics: Beauty as Resistance

Though protest art is political, aesthetics still play a crucial cultural role. Beauty in protest art can humanize suffering, build empathy, and transform anger into hope. Vivid colors, bold lines, and simplified icons help deliver powerful messages quickly. Symbols become unifying forces: raised fists, broken chains, peace doves, and slogans like “No Justice, No Peace” or “We Shall Overcome” serve both emotional and strategic functions. Protest art often blends beauty with trauma, using visual appeal to draw viewers into uncomfortable truths.

Performance art also uses the body as a canvas of resistance. Artists may stage acts of vulnerability, endurance, or symbolic pain to represent collective trauma. Protest performances in Chile, such as the feminist collective Las Tesis’ choreography “Un violador en tu camino”, use movement and chanting to expose gender violence. Such performances become cultural rituals, linking bodies with political expression.

The Commercialization of Protest Art

Despite its radical roots, modern protest art faces increasing commercialization. Fashion brands use political slogans, artworks, and revolutionary imagery to sell products. Banksy’s art, originally anti-capitalist, is now auctioned for millions. Protest posters from the 1960s and 1970s hang in luxury galleries. Digital protest art is copied without credit and circulated as merchandise. This commodification raises ethical questions: Can art remain revolutionary if it becomes profitable? Does commercialization dilute the message or spread it more widely?

Some argue that commercialization can expose more people to important issues. Others believe it exploits suffering for aesthetic pleasure and consumerism. Many protest artists remain anonymous or refuse commercial partnerships to preserve integrity. The tension between radical message and market value continues to shape protest art culture.

The Future of Protest Art

As long as injustice persists, protest art will continue evolving. Climate change, migration crises, artificial intelligence, surveillance capitalism, and digital authoritarianism will inspire new forms of resistance. Artists may use augmented reality, holograms, AI-generated graphics, blockchain ownership, and decentralized platforms to bypass censorship and control. Future protest art may not only depict rebellion—it may reshape political systems by challenging how we see, share, and control information.

Across cultures, modern protest art remains deeply human. It captures grief, anger, solidarity, and hope. It honors those who have suffered and empowers those who continue to resist. It is a cultural language that transcends borders, and a historical archive that documents the battles of our time. In every era, protest art teaches us that art is not merely decoration; it is a weapon, a shield, and a voice. It amplifies the marginalized, exposes the corrupt, and reminds society that change begins not only in parliament or courtroom but also on a canvas, a street wall, a song, or a digital screen.