Dark Art Culture occupies a distinct and often controversial place within the broader spectrum of artistic expression. Rooted in an aesthetic of the macabre, the unsettling, and the taboo, it explores the shadowed aspects of human existence that many prefer to ignore. Rather than focusing on beauty in a traditional sense, Dark Art is preoccupied with the grotesque, the melancholic, the supernatural, and the psychologically disturbing. Its practitioners and admirers argue that darkness itself possesses beauty and meaning, revealing truths about mortality, fear, and the human condition. The culture surrounding Dark Art has evolved over centuries, drawing on themes from Gothic literature, Romanticism, death rituals, psychological horror, and countercultural movements. In the modern era, it continues to thrive across diverse media—from painting and sculpture to digital art, fashion, tattoo design, and music—reflecting society’s ongoing fascination with the morbid and the mysterious.

Origins and Historical Development

The origins of Dark Art Culture can be traced back to early human fascination with death and the supernatural. Prehistoric cave paintings depicting hunting scenes and death rituals already showed an interest in mortality and transformation. However, the foundations of what would later be recognized as Dark Art emerged most visibly during the Middle Ages, a time marked by plague, famine, and religious obsession with sin and salvation. Medieval art frequently depicted scenes of suffering, martyrdom, and apocalypse, not only to convey moral lessons but also to confront the omnipresence of death. The “Danse Macabre,” or “Dance of Death,” for example, illustrated skeletons leading people from all walks of life to the grave, reminding viewers that death was universal and inescapable.

During the Renaissance, a more humanistic yet equally dark fascination developed with anatomy, decay, and vanitas—the transience of life and the futility of earthly pleasures. Artists like Hans Holbein the Younger created works that intertwined beauty with death, revealing the tension between physical perfection and inevitable decomposition. In the Baroque period, artists such as Caravaggio employed dramatic lighting and emotional intensity to portray scenes of violence, suffering, and divine punishment, setting a precedent for later explorations of darkness as an aesthetic mode.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a transformation of Dark Art into a more psychological and literary form through the Gothic movement. Writers such as Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, and Bram Stoker translated visual and architectural darkness into narrative and emotional experiences. Their tales of monsters, haunted castles, and tragic obsession influenced visual artists and provided a new cultural language for expressing the sublime terror of existence. Romantic painters like Francisco Goya and Henry Fuseli further expanded the dark imagination, illustrating nightmares, madness, and moral corruption with a raw emotional force that shocked their audiences.

By the 20th century, Dark Art had become deeply intertwined with existentialism, psychoanalysis, and modern alienation. The horrors of world wars, the rise of surrealism, and the exploration of the unconscious by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung all contributed to a cultural landscape in which darkness represented not just fear but self-knowledge. Artists such as Salvador Dalí, H. R. Giger, and Francis Bacon drew upon these ideas to expose the inner torment and fragmentation of the modern psyche. This period marked the beginning of Dark Art as both a psychological and philosophical pursuit rather than merely an aesthetic one.

Philosophical Foundations of Dark Art Culture

Dark Art Culture is underpinned by philosophical concepts concerning death, decay, duality, and the unconscious. At its core lies the belief that darkness is not inherently evil but is instead a necessary complement to light—a perspective rooted in the principle of dualism. In Jungian psychology, the “shadow” represents the suppressed and hidden parts of the self that one must confront to achieve wholeness. Dark Art, therefore, becomes a visual and symbolic means of exploring the shadow, providing catharsis and insight through confrontation with the grotesque or forbidden.

Another key philosophical underpinning is existentialism. The inevitability of death and the seeming meaninglessness of life are recurrent motifs in Dark Art. Artists working in this mode often seek to depict the fragility of human existence, the anxiety of being, and the longing for transcendence. Rather than offering solutions, Dark Art invites viewers to dwell in the discomfort of mortality and moral ambiguity. This confrontation with the void can produce either despair or enlightenment—depending on the viewer’s willingness to accept the darker aspects of reality.

Nietzsche’s concept of the Dionysian spirit also resonates within Dark Art Culture. It celebrates chaos, passion, and the ecstatic destruction of order, reflecting humanity’s instinctual and primal side. Dark Art often defies societal taboos, pushing boundaries of taste and morality to challenge conventions and expose hypocrisy. By doing so, it functions as both critique and liberation, offering an alternative vision of beauty rooted in imperfection, entropy, and emotional truth.

Themes in Dark Art

While Dark Art Culture encompasses a wide array of media and interpretations, certain recurring themes define its essence and distinguish it from mainstream artistic traditions. These include death and mortality, the grotesque and the uncanny, madness and the psyche, religious and occult symbolism, and social and existential rebellion.

Death and Mortality

Death is the central theme of Dark Art. It is both a subject and a symbol—a reminder of impermanence and a call to contemplate what lies beyond. In traditional vanitas paintings, skulls, hourglasses, and decaying fruit served as memento mori (“remember you must die”) symbols, urging humility and reflection. Contemporary Dark Art continues this dialogue but with a more secular and sometimes ironic tone. Artists like Damien Hirst, with his preserved animal corpses, and Joel-Peter Witkin, with his surreal photographic tableaux, use death as a lens to examine human vanity, denial, and the commodification of mortality.

The fascination with death also extends to the aestheticization of decay. Many Dark Art pieces embrace the beauty of deterioration—rusted metal, crumbling architecture, withered flowers—suggesting that entropy itself is an artistic process. In doing so, they subvert traditional ideas of beauty as perfection and permanence, replacing them with an appreciation of imperfection and temporality.

The Grotesque and the Uncanny

The grotesque is another defining characteristic of Dark Art, merging the horrific and the humorous, the human and the monstrous. By distorting familiar forms, grotesque imagery unsettles viewers and compels them to reconsider their assumptions about normality. The uncanny, as described by Sigmund Freud, arises when something familiar is rendered strange—such as lifelike dolls, corpses, or distorted human figures. Dark Art frequently employs this psychological tension to evoke unease and fascination simultaneously.

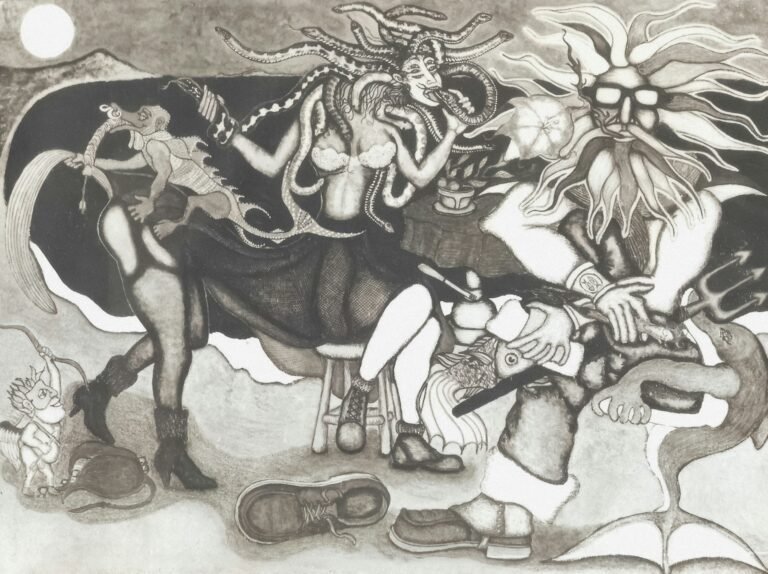

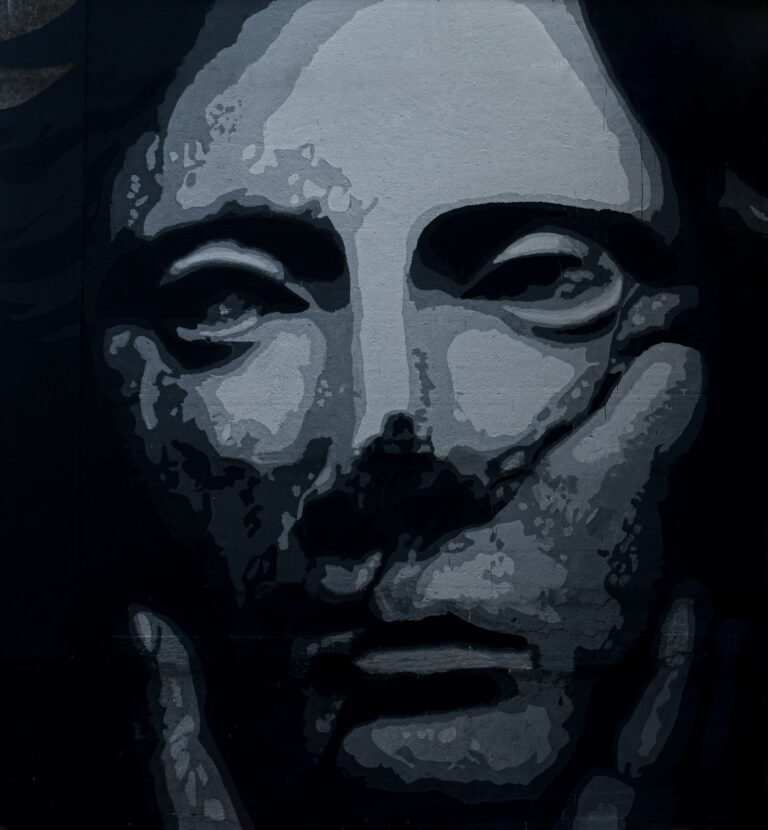

- R. Giger’s biomechanical hybrids, for example, combine sensuality and revulsion, exploring the blurred boundaries between flesh and machine. Similarly, the surrealist paintings of Zdzisław Beksiński create nightmarish dreamscapes where skeletal figures wander through desolate worlds. These works do not simply aim to shock but to mirror the subconscious mind, exposing the fears and desires that lie beneath rational control.

Madness, Dreams, and the Psyche

Dark Art often delves into the psychological dimensions of madness, trauma, and the irrational. Drawing inspiration from Freud’s theories of dreams and the unconscious, many artists use nightmarish imagery to visualize mental states that cannot be expressed through ordinary language. Madness, in this context, is not merely a medical condition but a metaphor for creative and spiritual awakening. It represents the breaking of boundaries—between sanity and insanity, reason and chaos, self and other.

Francis Bacon’s tortured figures and distorted portraits epitomize this exploration of psychological anguish. Their smeared faces and contorted bodies embody the fragility of identity and the violence of emotion. Similarly, contemporary digital and mixed-media artists use fragmented compositions and glitch aesthetics to express the fractured consciousness of modern life. By visualizing inner turmoil, Dark Art provides a space for empathy and introspection, challenging stigmas around mental health and difference.

Religious and Occult Symbolism

Religion and the occult play a significant role in Dark Art Culture, not necessarily as expressions of faith but as symbols of mystery, power, and transgression. Medieval and Renaissance depictions of hell, angels, and demons established a rich iconography that continues to inspire modern artists. However, contemporary Dark Art often reinterprets these symbols through a critical or rebellious lens, questioning institutional authority and the moral binaries of good versus evil.

Occult themes—alchemy, witchcraft, tarot, and mysticism—serve as metaphors for transformation and hidden knowledge. The figure of the witch or the fallen angel becomes an emblem of resistance against patriarchal or dogmatic systems. Aleister Crowley’s esoteric teachings and the symbolism of secret societies like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn have influenced many 20th- and 21st-century dark artists who see magic as a metaphor for creative empowerment.

Rebellion and Counterculture

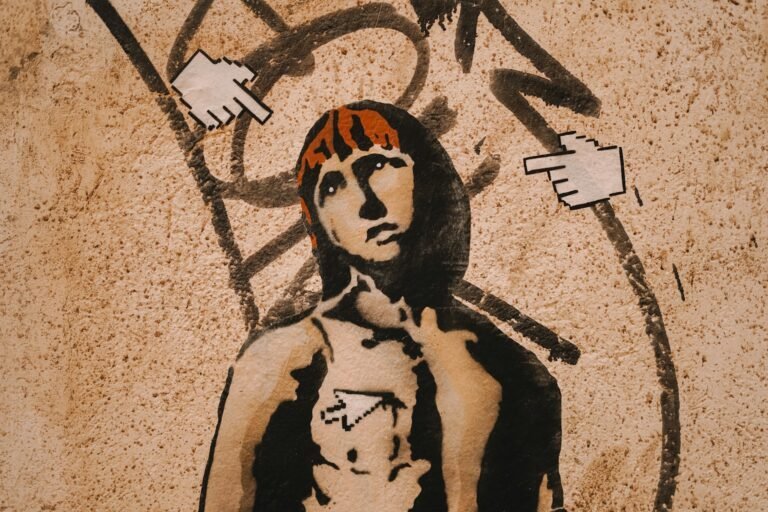

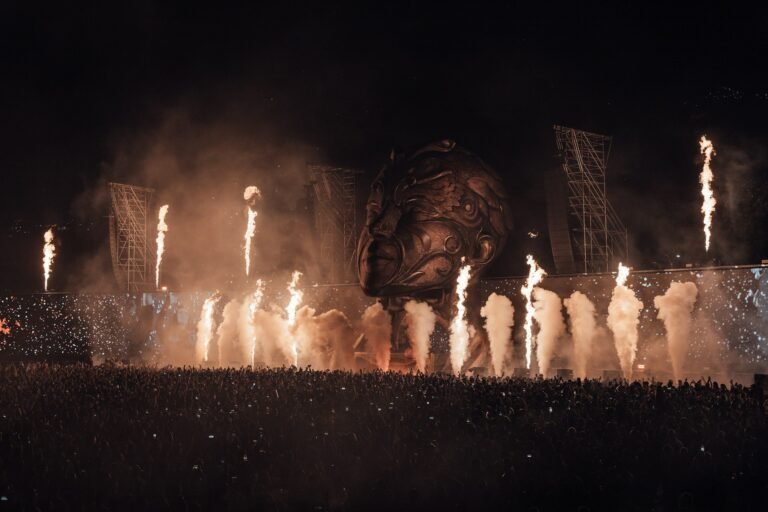

Dark Art Culture has always been intertwined with rebellion—against social norms, aesthetic conventions, and political complacency. In the late 20th century, it found new expression in subcultures such as punk, goth, industrial, and metal music scenes. Album covers, tattoos, and underground zines became canvases for dark aesthetics, merging art with identity. Artists and fans alike adopted macabre imagery to express alienation, resistance, and individuality in the face of conformity.

This countercultural dimension of Dark Art extends beyond mere shock value. It represents a critique of consumerism, moral hypocrisy, and superficial beauty standards. The dark aesthetic, by embracing imperfection and discomfort, becomes a protest against a culture obsessed with positivity and denial of suffering. In this sense, Dark Art is not nihilistic but profoundly human—it acknowledges pain as part of existence and transforms it into creative expression.

Dark Art in Contemporary Media

In the digital age, Dark Art has expanded beyond galleries into popular and virtual culture. The rise of horror cinema, dark fantasy, and digital illustration has democratized access to macabre imagery, allowing artists to reach global audiences. Films such as Pan’s Labyrinth, The Witch, and Hereditary exemplify cinematic Dark Art, combining visual beauty with existential dread. Video games like Dark Souls and Bloodborne transform this aesthetic into interactive experiences, inviting players to inhabit worlds of decay and despair while seeking meaning through struggle.

Social media platforms and online galleries have also fostered a vibrant community of dark artists and collectors. Websites like DeviantArt, Instagram, and ArtStation feature thousands of creators exploring horror, surrealism, and occult themes. This digital ecosystem has blurred the boundaries between fine art, illustration, and fashion. Dark Art now influences tattoo design, gothic clothing, music videos, and even commercial branding. What was once underground has become a recognized and lucrative genre, though it still retains its transgressive and introspective core.

Gender, Identity, and the Body in Dark Art

Dark Art frequently engages with the human body as both a site of beauty and corruption, desire and decay. For women and queer artists, this has provided a means to challenge traditional representations of the body and reclaim agency through darkness. Feminist Dark Art explores themes of bodily autonomy, sexuality, and trauma, often using horror imagery to critique patriarchal violence. Artists such as Jenny Saville and Marina Abramović, though not always categorized strictly as “dark artists,” use corporeal imagery to confront societal taboos around blood, flesh, and vulnerability.

Similarly, queer Dark Art uses gothic and surreal aesthetics to explore identity, transformation, and otherness. The monstrous becomes a metaphor for marginalization and resilience. By embracing what mainstream culture fears or rejects, these artists turn darkness into empowerment, redefining what it means to be human.

Dark Art and the Sublime

One of the most profound aesthetic concepts underpinning Dark Art is the sublime—the feeling of awe mixed with terror when confronted with vastness, chaos, or mortality. This concept, developed by philosophers such as Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant, describes the paradoxical beauty found in fear and destruction. Dark Art often aims to evoke the sublime through scale, atmosphere, and emotional intensity. Whether in a haunting landscape, a colossal sculpture, or an immersive digital installation, the viewer experiences both attraction and repulsion, insignificance and transcendence.

Through the sublime, Dark Art elevates the macabre to a spiritual experience. It transforms fear into fascination, showing that darkness is not simply the absence of light but a realm of profound revelation.

Ethics and Controversy

Dark Art’s engagement with taboo subjects often provokes controversy. Critics accuse it of glorifying violence, morbidity, or nihilism, while defenders argue that it serves as a mirror to society’s suppressed truths. The ethical question lies in intention and interpretation. A depiction of suffering can be exploitative or empathetic depending on context. Many artists within the Dark Art community emphasize that their work seeks to provoke reflection rather than desensitization. By confronting horror symbolically, they aim to process trauma and explore moral complexity rather than celebrate brutality.

Moreover, Dark Art raises questions about censorship and freedom of expression. Because it often challenges religious or political boundaries, it becomes a battleground for debates about artistic responsibility and public sensitivity. Yet, throughout history, art that confronts discomfort has proven essential for cultural growth and psychological healing. The darkness of art, therefore, should not be feared but understood as part of the full spectrum of creative inquiry.

Dark Art as Catharsis and Healing

Despite its grim appearance, Dark Art often functions as a form of therapy—for both creators and viewers. It allows individuals to externalize pain, anxiety, and grief in a symbolic and controlled environment. Psychologists have noted that engaging with dark imagery can provide catharsis, helping people confront and process emotions they might otherwise repress. In this sense, Dark Art becomes a ritual of transformation: it turns suffering into meaning, fear into understanding, and chaos into beauty.

This therapeutic dimension explains why Dark Art resonates with audiences during times of crisis. In a world marked by environmental degradation, war, and existential uncertainty, the aesthetics of darkness speak to collective trauma and resilience. By acknowledging despair rather than denying it, Dark Art offers an honest form of hope—the hope that through facing darkness, one can rediscover light.

Conclusion

Dark Art Culture is far more than an indulgence in horror or morbidity. It is a multifaceted exploration of the human condition, uniting philosophy, psychology, and aesthetics in its confrontation with the unknown. From medieval visions of death to digital nightmares of the 21st century, Dark Art continues to challenge the boundaries of beauty, morality, and meaning. Its themes—mortality, madness, the grotesque, rebellion, and transcendence—mirror our deepest fears and desires. By gazing into the abyss, Dark Art does not lead us to despair but to awareness, reminding us that darkness and light are inseparable aspects of existence.

Ultimately, Dark Art Culture invites us to see beauty in the shadows and truth in the terrifying. It transforms fear into fascination, chaos into creativity, and death into dialogue. In doing so, it reaffirms art’s most essential function: to illuminate the hidden dimensions of the human soul.