A Book of Hours is a type of Christian devotional manuscript that was especially popular in Western Europe from the late Middle Ages (roughly the 13th to the early 16th century). It was designed primarily for laypeople, not clergy, and served as a personal guide to prayer and meditation throughout the day. Named after the “canonical hours” of prayer observed by monks and nuns, the Book of Hours adapted these structured religious practices for private use in homes. Over time, it became the most common book owned by medieval Christians and one of the most significant artifacts of medieval religious, artistic, and social life.

The origins of the Book of Hours lie in the monastic tradition of daily prayer. In monasteries, monks followed a strict schedule known as the Divine Office, which divided the day into specific prayer times called hours: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. These prayers were traditionally contained in large and complex liturgical books such as breviaries and psalters, which required education and training to use. As Christianity spread and literacy among laypeople slowly increased, especially among the nobility and urban elites, there arose a desire for simplified devotional texts that ordinary believers could use without formal religious training. The Book of Hours emerged to meet this need.

A typical Book of Hours contained a set structure, though individual examples varied depending on region, patron, and personal preference. The core text was usually the Hours of the Virgin Mary, a cycle of prayers dedicated to the Virgin Mary to be read at different times of the day. This section reflected the central role of Mary in medieval devotion, as she was viewed as a compassionate intercessor between humanity and God. In addition to the Hours of the Virgin, most Books of Hours included a calendar of saints’ days, which helped the owner track important religious feasts throughout the year. These calendars often highlighted local saints, revealing where the book was made or intended to be used.

Another common component was the Penitential Psalms, a group of seven psalms traditionally associated with repentance and humility. These psalms were often accompanied by prayers asking for forgiveness of sins and divine mercy. Closely related were the Litany of the Saints, which listed saints in a specific order and asked each to pray on behalf of the reader. The final major section was the Office of the Dead, a set of prayers intended for the souls of the deceased. This section reflected medieval beliefs about purgatory and the importance of prayer in helping souls achieve salvation. Through these components, the Book of Hours guided its user through a comprehensive spiritual life centered on prayer, reflection, and remembrance.

The primary use of the Book of Hours was private devotion. Unlike large church books meant to be read aloud during communal worship, the Book of Hours was portable and personal. Owners could read it quietly at home, while traveling, or even in church during services. It allowed individuals to structure their day around prayer, aligning their daily routines with sacred time. For many medieval Christians, especially women, the Book of Hours provided an important means of religious participation in a society where access to formal theological education and clerical roles was limited.

Beyond its religious function, the Book of Hours also served as a tool for moral instruction and spiritual discipline. The prayers emphasized virtues such as humility, patience, charity, and obedience, reinforcing the moral framework of medieval Christianity. By regularly reading and meditating on these texts, users were encouraged to examine their conscience, repent of sins, and strive for spiritual improvement. In this sense, the Book of Hours functioned not only as a prayer book but also as a guide for shaping one’s inner life according to Christian ideals.

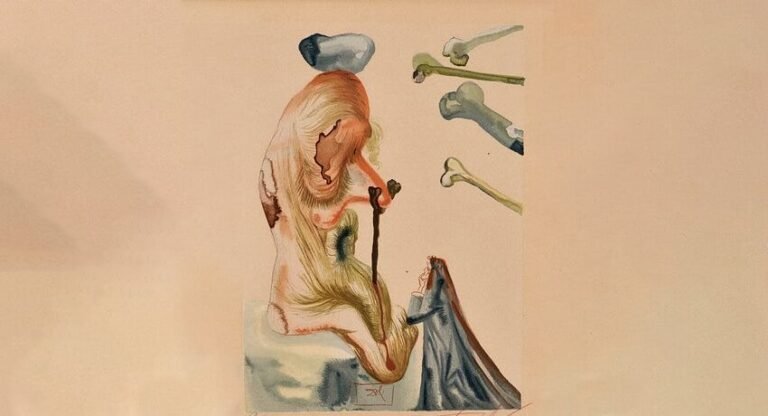

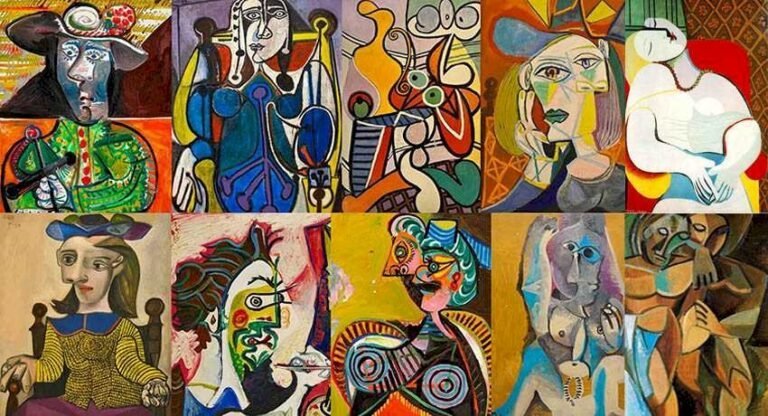

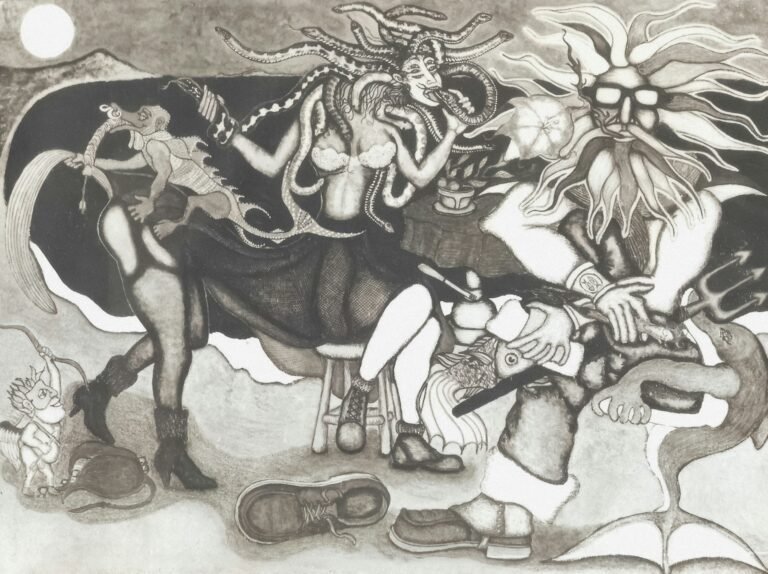

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Book of Hours is its artistic richness. Many were lavishly illuminated with gold leaf, vibrant pigments, and intricate designs. These illuminations included full-page miniatures depicting scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints, as well as decorative borders filled with flowers, animals, and fantastical creatures. The visual imagery served several purposes. It enhanced the beauty and value of the book, reflected the wealth and status of the owner, and aided devotion by providing visual focal points for meditation. In an era when many people were only partially literate, images played a crucial role in conveying religious meaning.

The production of Books of Hours supported a complex network of artisans, including scribes, illuminators, parchment makers, and binders. Early examples were entirely handmade and extremely expensive, making them luxury items accessible mainly to royalty and the nobility. Over time, however, advances in manuscript production and later the invention of printing made simpler Books of Hours more affordable. By the 15th century, they were owned by merchants, professionals, and even some peasants, making the Book of Hours one of the first “mass-market” books in European history.

The Book of Hours also had a significant social and cultural function. It was often given as a gift to mark important life events such as marriages, births, or coming of age. Many included personalized elements, such as the owner’s name, coat of arms, or portraits of family members depicted kneeling in prayer. These features turned the Book of Hours into a family heirloom, passed down through generations. Marginal notes sometimes recorded births, deaths, and marriages, making these books valuable historical documents that provide insight into medieval family life.

For women in particular, the Book of Hours played a crucial role in religious and intellectual life. In a society where women’s access to formal education was limited, devotional reading offered one of the main avenues for literacy. Many women learned to read using their Book of Hours, which was often written in Latin but sometimes included vernacular translations or explanations. The emphasis on the Virgin Mary also resonated strongly with female readers, offering a powerful model of devotion, motherhood, and spiritual authority.

The Book of Hours was also deeply connected to medieval ideas about time. By dividing the day into sacred hours, it encouraged users to see time itself as structured by God. Everyday activities such as work, meals, and rest were framed within a rhythm of prayer. This way of experiencing time reinforced the belief that human life should be oriented toward the divine. The calendar section, with its cycle of feasts and fasts, further linked personal devotion to the broader liturgical year of the Church.

With the arrival of the printing press in the mid-15th century, the Book of Hours entered a new phase. Printed editions retained many features of manuscript versions, including decorative borders and illustrations, but could be produced more quickly and cheaply. Printers such as Philippe Pigouchet in Paris created highly popular printed Books of Hours that combined text and woodcut images. These printed versions spread devotional practices even more widely and contributed to rising literacy rates across Europe.

However, the popularity of the Book of Hours began to decline during the 16th century, particularly with the Protestant Reformation. Reformers criticized certain aspects of traditional Catholic devotion, including prayers to saints and the Office of the Dead. In Protestant regions, Books of Hours were replaced by other devotional texts, such as psalm books and Bibles in the vernacular. In Catholic areas, they continued to be used, but new forms of prayer books gradually took their place.

Today, Books of Hours are highly valued by historians, art historians, and collectors. They provide rich evidence of medieval religious beliefs, artistic styles, daily life, and social structures. Famous examples, such as the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, are considered masterpieces of medieval art. Museums and libraries around the world preserve these books as cultural treasures, and digital projects have made many of them accessible to modern audiences.

In summary, the Book of Hours was a personal devotional book used by medieval Christians to pray at set times throughout the day. Rooted in monastic prayer traditions but adapted for lay use, it structured daily life around spiritual reflection, reinforced moral values, and expressed deep devotion to God, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. At the same time, it functioned as a work of art, a status symbol, an educational tool, and a family record. Its widespread use and enduring legacy make the Book of Hours one of the most important and influential books of the Middle Ages.