Installation art is one of the most influential and immersive developments in contemporary art, emerging prominently during the twentieth century and continuing to evolve in the twenty-first century. Unlike traditional art that is confined to a defined frame or pedestal—such as painting on canvas or sculpture on a plinth—installation art transforms entire spaces into expressive, communicative environments. These works are not mere objects to look at; rather, they are complete sensory worlds that spectators enter, experience, and interpret with their bodies, emotions, and minds. The movement challenges the conventional boundaries of art by asking viewers to participate actively in the artwork instead of passively observing it. In doing so, installation art blurs distinctions between artistic mediums, expands aesthetic expectations, and redefines the relationship between viewer, object, and environment.

Origins and Historical Context

Although the term installation art became commonly used in the late twentieth century, its conceptual roots can be traced to avant-garde movements of the early 1900s. Movements such as Dada, Futurism, Constructivism, and Surrealism pioneered ideas that later shaped installation practice. For example, Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp challenged the importance of artistic skill and traditional craftsmanship by introducing readymade objects into the art world. His famous work Fountain (1917), which presented a urinal as art, introduced a radical conceptual approach that valued the idea over the artistic technique. This notion later became central to installation art, where the meaning or concept often outweighs material aesthetics.

After World War II, new experimental forms emerged, especially with the birth of happenings and performance art in the 1960s. Artists such as Allan Kaprow created “environments” and “happenings,” in which ordinary objects, public participation, and everyday actions became artistic tools. These activities emphasized experience over object-making, paving the way for large-scale, immersive installations. At the same time, Minimalist and Conceptual artists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Joseph Kosuth began to explore spatial, sculptural, and idea-based works, rejecting traditional art boundaries. Their experiments reinforced a shift toward art that occupied space as a living presence instead of functioning as a self-contained object.

By the late twentieth century, installation art became a recognized artistic practice. It was particularly embraced by artists who sought innovative means to address social, political, cultural, and environmental issues. Museums and galleries started dedicating entire rooms for installations, and temporary, site-specific works emerged in outdoor locations, abandoned buildings, and public spaces. The movement thus expanded beyond traditional exhibition models and questioned the institutional power of museums and galleries. Today, installation art continues to flourish, influenced by digital technology, globalization, environmental activism, and interactive media.

Defining Characteristics of Installation Art

One of the most distinctive features of installation art is its emphasis on space. Unlike painting or conventional sculpture that exists independently of its setting, installation art transforms the environment itself into a key component of the artwork. The interaction between site and artwork—even down to the lighting, architecture, sounds, smells, and materials—plays a crucial role in shaping meaning. This spatial emphasis means that installations cannot always be relocated without altering their identity. Some works are site-specific, meaning they are designed exclusively for a particular location and lose relevance or coherence when moved. Artists may respond to historical, environmental, or social aspects of a site, allowing the place to participate in the creation of meaning.

Another defining feature is the use of diverse materials and media. Installation artists are not restricted to traditional art supplies such as paint or clay. Instead, they employ everyday objects, technological devices, natural elements, found items, sound equipment, video projections, and even living organisms. This diversity reflects the movement’s rejection of artistic hierarchy and its embrace of experimentation. Some installations use fragile materials like paper or glass; others incorporate durable industrial objects like metal pipes or electronic machinery. Still others integrate non-material elements like sound, light, scent, or movement. These varied media help create immersive experiences in which viewers are enveloped and stimulated through multiple senses, not only sight.

Interactivity is also a significant aspect of installation art. Many installations invite, require, or provoke audience participation. Instead of looking at art from a distance, viewers may walk through it, touch it, manipulate its components, or influence outcomes through their physical presence. This participatory dimension destabilizes conventional roles: the viewer may become a co-creator, while the artwork transforms depending on audience behavior. In some cases, installations change or deteriorate with time, reinforcing the idea of temporality and unpredictability. Interactivity also encourages personal interpretation, suggesting that each person’s experience of the same installation may differ based on their movement, decisions, emotions, and memories.

Another important characteristic is conceptual emphasis. Installation art frequently prioritizes ideas over visual beauty. While some works can be aesthetically striking, many are designed primarily to provoke thought or elicit emotional reactions. Meaning arises from the relationships among objects, spaces, and viewers rather than traditional techniques such as painting styles or sculptural modeling. This conceptual focus challenges expectations that artworks must be visually pleasing or artistically “crafted.” Instead, installation art may present disturbing imagery, political messages, environmental warnings, or critical commentary that requires reflection and dialogue. In this sense, installation art often addresses contemporary social issues including consumerism, climate change, war, gender identity, globalization, migration, and technology.

Temporal and Ephemeral Qualities

Installation art is often temporary, highlighting a fundamental shift in artistic value. Unlike classical paintings or sculptures designed for permanence, many installations are constructed only for a brief exhibition period. They may be dismantled afterward or destroyed because they depend on specific materials, spaces, or conditions that cannot be preserved. Some are built with perishable items such as leaves, ice, food, or biodegradable matter that decay or disappear. Others depend on digital technology or performance elements that change over time. The ephemerality of installation art critiques consumerist notions of art as commodity. If an installation cannot be owned or easily sold, it resists commercialization and encourages audiences to value experience over possession.

This temporal nature also reflects modern society’s relationship with change, memory, and impermanence. Some installations reveal transformation in real time—melting ice sculptures, eroding clay structures, burning candles, or mechanical systems that deteriorate. These processes remind viewers of cycles of life, environmental destruction, or industrial decay. Because installations may exist only for a moment, they become valuable as lived experience rather than collectible objects. Museums that wish to preserve installation art often face dilemmas: they may attempt to reconstruct the work based on artist instructions, but questions arise about authenticity. This debate challenges the art world to rethink preservation methods and curatorial practices, expanding institutional interpretations of what art can be.

Installation Art and Public Space

Another essential dimension of installation art is its presence in public space. Many artists create works outside institutional confines, installing them in forests, streets, beaches, urban squares, or abandoned structures. These interventions democratize art by making it accessible to people who do not visit museums. Public installations may surprise pedestrians, disrupt everyday routines, or invite interactions from random passersby. Because they exist in shared environments, these works sometimes engage directly with local culture, historical context, or political conflicts. They can critique state power, consumer culture, environmental exploitation, or social inequality, becoming tools of activism and public dialogue.

Public installations, because they are exposed to weather, vandalism, or unexpected interactions, also highlight unpredictability. They might be altered, damaged, or appropriated by the public, blurring boundaries between artist intent and public use. This openness distinguishes installation art from conventional monuments that communicate fixed messages. Instead, installation art evolves alongside its surroundings and the people who encounter it, emphasizing collective interpretation.

The Role of Technology in Installation Art

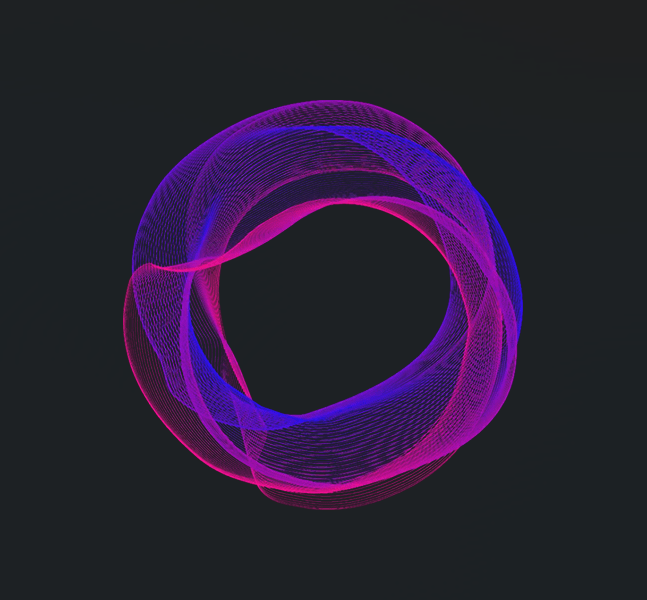

In recent decades, technological advancements have expanded the possibilities of installation art. Many artists integrate video projections, artificial intelligence, interactive digital screens, robotics, augmented reality, or virtual reality. Such works respond to contemporary questions about human-machine relationships, surveillance, media consumption, and digital identity. Sound installations use recorded or live audio to shape spatial perceptions, while light installations employ projectors, neon tubing, or laser beams to transform architectural environments. Technological installations may react to audience movement through sensors that change light, sound, or motion, producing real-time experiences that cannot be replicated.

These integrations highlight how installation art adapts to changing cultural conditions. As technology shapes modern life, artists use it to question its influence: how does digital media transform human relationships? What are the ethical implications of artificial intelligence? How is truth manipulated through virtual imagery? By embedding these issues into immersive environments, installation art encourages viewers to confront them through bodily and sensory engagement rather than abstract discussion.

Installation Art and Cultural Identity

Installation art frequently addresses questions of identity, memory, and cultural history. Artists use space and objects to represent collective trauma, diaspora, social marginalization, gender struggles, religious rituals, or indigenous heritage. Installations that incorporate personal belongings, archival materials, or symbolic objects can evoke emotional responses that connect individual experience to broader narratives. For example, installations that use clothing may represent absence, migration, or violence; those that use soil, seeds, or natural materials might explore cultural attachment to land, ecological destruction, or spiritual traditions.

Many installation artists draw on local customs or indigenous knowledge, challenging Western dominance in the art world. By using community objects, oral histories, or participatory events, they reshape museum and gallery spaces into sites of cultural negotiation. These practices question whose history is displayed, who is allowed to speak, and how cultural memory is preserved. Installation art thus becomes a powerful medium for reclaiming marginalized voices and asserting collective identity.

Viewer Experience and Psychological Impact

Since installation art creates immersive spaces, the viewer’s psychological experience is central. Some works evoke tranquility and contemplation through minimal design, soft light, or meditative sound. Others provoke discomfort, fear, or shock by using dark environments, claustrophobic spaces, or distressing imagery. The spatial encounter becomes a journey that engages bodily movement, sensory reaction, and emotional interpretation. Unlike paintings that can be understood from a single viewpoint, installations require viewers to navigate physically, creating shifting perspectives.

This experiential emphasis invites personal interpretation. The presence of the viewer completes the artwork, meaning that no two experiences are identical. Each person brings their own memories, beliefs, and emotions, altering their engagement. This subjectivity reinforces the movement’s rejection of fixed meaning. Instead, installation art prioritizes experiential knowledge—art becomes something one feels, not just sees.

Conclusion

Installation art represents a profound shift in how art is created, displayed, and understood. By transforming space into an expressive medium, using diverse materials, encouraging interactivity, and embracing temporality, installation art challenges traditional artistic definitions. It confronts issues of technology, identity, environment, politics, and public engagement, expanding the purpose of art beyond aesthetic appreciation. Installation art emphasizes experience over object, participation over passive observation, and conceptual depth over visual perfection. Its growth reflects a changing cultural landscape in which art is no longer a commodity to be owned but an experience to be lived.

Through its immersive, experimental, and interdisciplinary nature, the installation art movement continues to redefine the boundaries of creative expression. It not only invites audiences to encounter art differently but also to rethink the world around them. In doing so, installation art transcends the limitations of conventional mediums, becoming a dynamic and transformative force that connects people, spaces, ideas, and emotions. As contemporary society continues to evolve, installation art will remain an influential platform for questioning norms, sparking dialogue, and shaping the future of aesthetic experience.