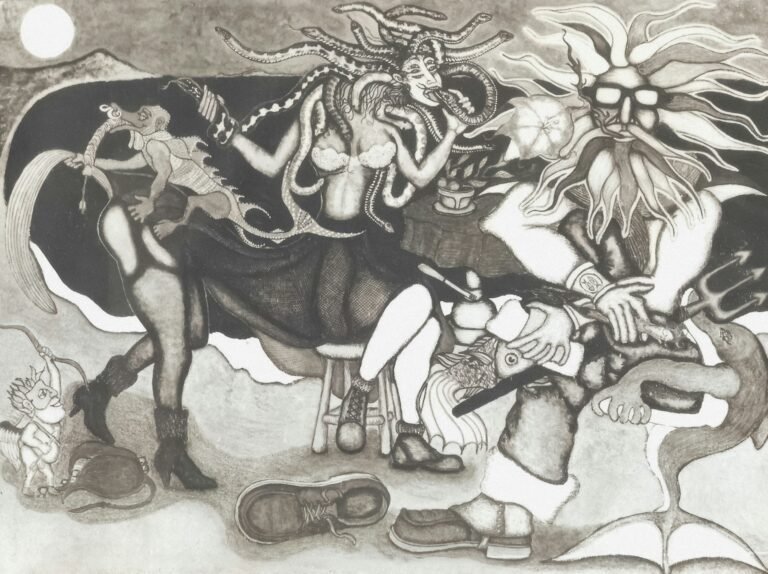

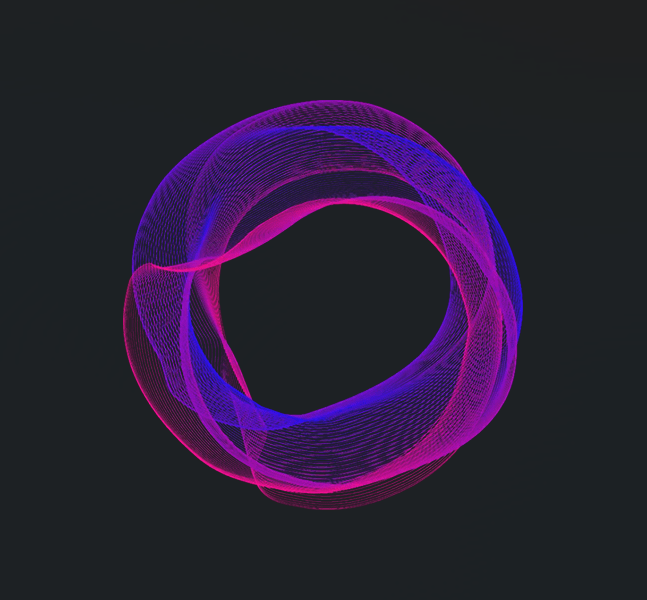

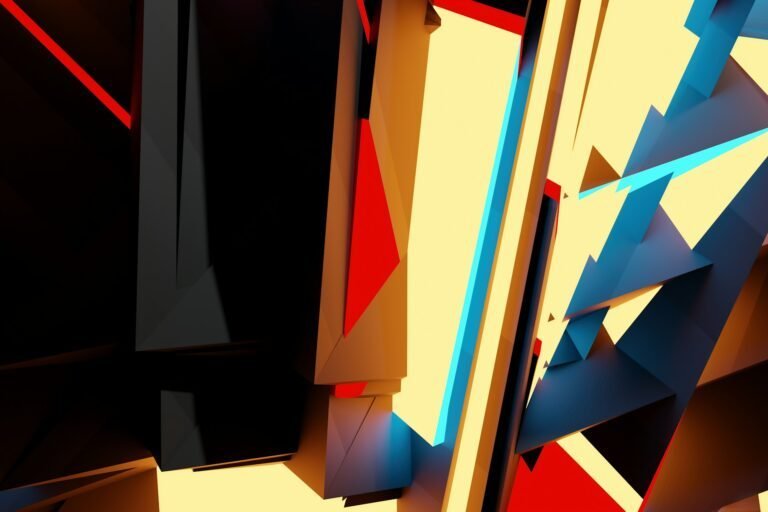

The value element of art pertains to the relative lightness or darkness of colors and tones within an artwork. It is a crucial aspect because it helps to create contrast, depth, and visual interest, allowing viewers to distinguish between different shapes and forms. By effectively manipulating value, artists can simulate the effects of light and shadow, making objects appear three-dimensional and realistic. Additionally, value can set the mood or emotional tone of an artwork; for example, darker values might evoke feelings of somberness or mystery, while lighter values can suggest brightness and optimism. Artists often use a range of values, from stark blacks to pure whites, to emphasize focal points and guide the viewer’s eye through the composition. Mastery of value is fundamental in creating a sense of volume, space, and atmosphere, making it an essential element in the language of visual art.

Art is a universal language that communicates emotions, ideas, and perceptions through visual expression. It uses several foundational elements that work together to create harmony and meaning within a composition. Among these elements—such as line, shape, form, color, texture, and space—the element of value holds a particularly vital place. Value refers to the lightness or darkness of a color or tone. It helps artists create depth, volume, and emphasis, guiding the viewer’s attention across the artwork. While color captures emotion and line defines shape, value is what gives an artwork its sense of reality and mood. Without value, an image would appear flat and lifeless. This essay explores the meaning, functions, and applications of value in art, illustrating its profound impact on visual perception, composition, and expression.

Definition and Concept of Value in Art

In the simplest terms, value is the degree of lightness or darkness in a color. Artists use a range of values—from pure white to deep black—to represent light and shadow. The transition between these extremes creates what is known as a value scale, which typically consists of several steps or gradations between white and black. Each step represents a different tone, helping artists to organize and control how light interacts with forms within a composition.

Value does not only exist in grayscale artwork such as pencil drawings or charcoal sketches; it also plays a crucial role in color artworks. Even when working with vivid hues, artists must consider how light or dark those colors appear. For example, yellow typically has a high value (appears lighter), while blue or violet has a low value (appears darker). When artists convert a colored image to grayscale, they can easily see the underlying value structure—revealing how brightness and contrast shape the image’s overall impact.

Value is one of the seven formal elements of art, and it is indispensable for creating a sense of three-dimensionality. It gives volume to forms, suggests texture, and enhances realism. Without value contrast, the shapes in a painting or drawing would blend together, making it difficult for the eye to distinguish one area from another. Thus, value acts as the foundation upon which all visual dynamics rest.

Historical Context of Value in Art

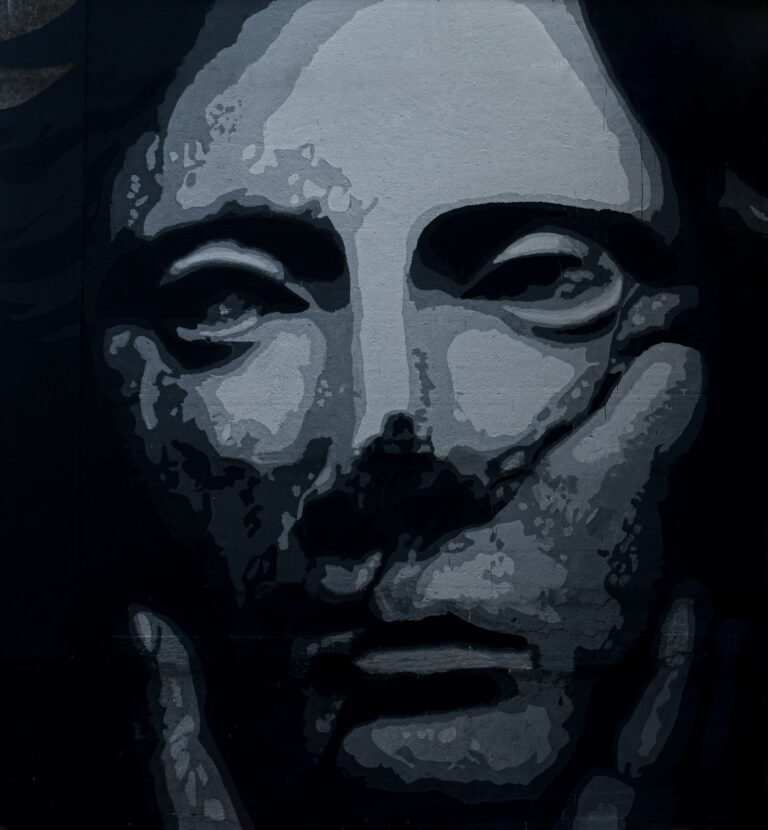

Throughout art history, the understanding and manipulation of value have evolved alongside changes in artistic style and technique. During the Renaissance, artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael developed sophisticated systems for depicting light and shadow, a method known as chiaroscuro. The term “chiaroscuro” comes from the Italian words for “light” (chiaro) and “dark” (scuro), and it refers to the use of strong contrasts between light and dark to model forms and create dramatic effects. Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa,” for instance, is a masterful example of chiaroscuro, where subtle gradations of value bring depth and mystery to the sitter’s face.

In the Baroque period, artists such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt further refined the use of value to create emotional intensity and theatrical illumination. Their compositions often used extreme contrasts—known as tenebrism—where figures emerge dramatically from dark backgrounds under intense light. This manipulation of value became a powerful storytelling tool.

During the 19th century, value also played a significant role in the works of Impressionists and Realists. Although the Impressionists, like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, focused on color and light rather than dramatic shading, they still relied on subtle shifts in value to capture atmosphere and time of day. In contrast, Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet used value to enhance naturalism and emphasize texture and form. In the 20th century, abstract artists like Pablo Picasso and Georgia O’Keeffe continued to explore value relationships as a means of structuring composition and emphasizing design rather than realism.

Value and Perception of Light

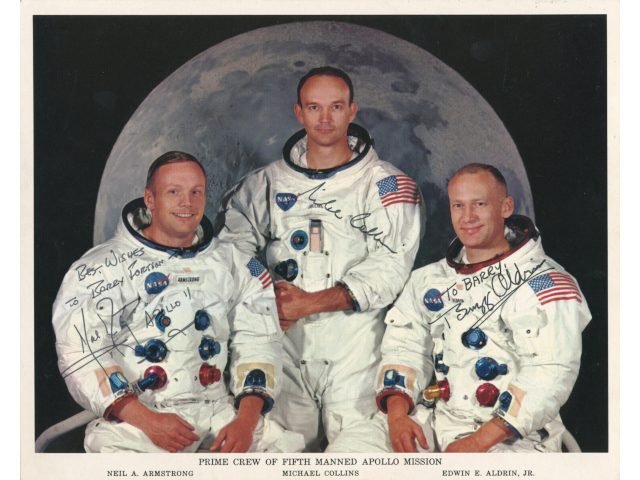

The human eye perceives objects primarily by detecting light reflected from their surfaces. The way light interacts with an object determines its highlights, mid-tones, and shadows—all of which contribute to the viewer’s perception of form. Value, therefore, is not just a technical concept; it mirrors how humans naturally interpret the world. When light falls on an object, the illuminated areas appear lighter, while areas in shadow appear darker. Artists study this relationship through value drawing—an exercise where they observe and record different tones created by light.

Understanding light and shadow is essential for achieving realism. Artists must analyze where the light source is located, how strong it is, and what direction it comes from. This determines where highlights (the lightest areas), core shadows (the darkest areas), and mid-tones (the transitional areas) will fall. For example, in portrait drawing, the accurate placement of shadows around the nose, eyes, and chin gives a sense of volume and character to the face. In landscape painting, changes in value convey time of day, weather conditions, and atmosphere.

The Value Scale

The value scale is a visual tool that helps artists measure and understand tonal relationships. It typically consists of a series of boxes or bars ranging from white to black, with several intermediate gray steps. These steps represent graduations of tone, each slightly darker than the previous one. Many artists use a 9-step or 10-step value scale, though it can be expanded or simplified depending on the medium.

By comparing areas of their artwork to the value scale, artists can ensure that their light and dark areas are balanced. This prevents the image from becoming too flat (if all values are similar) or too harsh (if contrast is too strong). The value scale also assists in identifying key value ranges, such as:

- High key: Dominated by light tones with minimal darks—often used to create an airy, delicate mood.

- Low key: Dominated by dark tones with few lights—used to create drama, mystery, or melancholy.

- Middle key: Balanced between light and dark—used to achieve harmony and naturalism.

Mastering the value scale allows artists to design compositions that are visually compelling and emotionally expressive.

Value Contrast and Visual Impact

Value contrast refers to the difference in lightness or darkness between two areas. High contrast creates strong visual impact and draws attention to focal points, while low contrast produces subtle, atmospheric effects. For instance, in photography and graphic design, high contrast is often used to highlight key subjects or create bold, dramatic compositions. In fine art, contrast can emphasize form, direct movement, or establish mood.

Artists manipulate value contrast to control emphasis and hierarchy within an artwork. The human eye is naturally attracted to areas of greatest contrast. Therefore, artists often place the lightest lights next to the darkest darks near the focal point to guide the viewer’s gaze. For example, in Rembrandt’s portraits, the face—particularly the eyes—is usually surrounded by rich shadows, making the illuminated features stand out with intensity. Conversely, soft transitions and limited contrast can evoke calmness and distance, as seen in Impressionist landscapes.

Creating Depth and Space with Value

One of the most important roles of value is to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. By skillfully adjusting light and dark areas, artists can simulate volume, depth, and atmospheric perspective. When an object is rendered with a full range of values—from bright highlights to deep shadows—it appears solid and lifelike. This process is known as modeling.

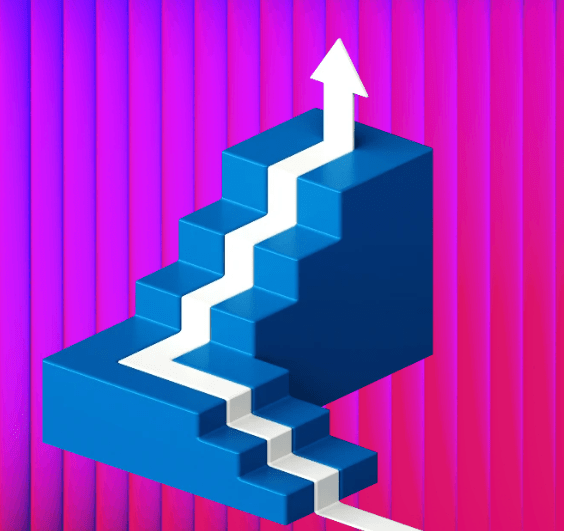

In addition, value helps convey spatial relationships between objects. Lighter values often appear to recede into the background, while darker values advance toward the viewer. This principle is evident in landscape art, where distant hills appear lighter and less detailed due to the scattering of light in the atmosphere—a phenomenon known as aerial perspective. By understanding and applying these visual cues, artists can create believable depth even on a flat canvas.

Value in Color Art

Although value is most clearly visible in black-and-white media, it is equally important in color artwork. Every color has an inherent value level, which affects how it interacts with other colors. For example, a bright yellow may have a similar value to a light gray, while a deep red might correspond to a dark gray. When two colors of similar value are placed side by side, they may appear to blend or lose distinction, even if their hues differ.

Therefore, successful color compositions depend not just on hue and saturation but also on value relationships. Painters often squint their eyes or view their work through a grayscale filter to assess whether their values are balanced. Understanding the value structure beneath the color allows artists to ensure that their compositions remain clear and visually effective even when color is removed. This principle can be seen in the works of artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet, whose vivid color palettes are supported by carefully planned value contrasts.

Techniques for Representing Value

Artists use a variety of techniques to create and control value in their work, depending on the medium:

- Hatching and Cross-Hatching: Drawing parallel lines (hatching) or intersecting lines (cross-hatching) to create shading in pencil or ink. The closer the lines, the darker the value appears.

- Stippling: Using small dots to build up tone; the density of dots determines the darkness.

- Blending: Gradually smoothing graphite, charcoal, or paint to transition seamlessly between light and dark areas.

- Scumbling and Glazing: In painting, layering thin washes of translucent color to adjust value without altering hue.

- Chiaroscuro: Employing strong contrasts between light and dark for dramatic three-dimensional effects.

- Tonal Blocking: Applying large areas of light or dark to define the general value structure before refining details.

Through practice, artists learn to control these methods to achieve realistic or expressive results.

Value in Different Art Forms

- Drawing:

In graphite, charcoal, or pen drawings, value defines form, light, and texture. Artists rely solely on tonal variation to express depth and emotion. - Painting:

In painting, value is crucial for color harmony and spatial illusion. Painters often do underpaintings in grayscale (called grisaille) before applying color glazes. - Photography:

Value is central to black-and-white photography, where contrast determines mood and composition. Photographers use lighting and exposure to manage tonal range. - Printmaking:

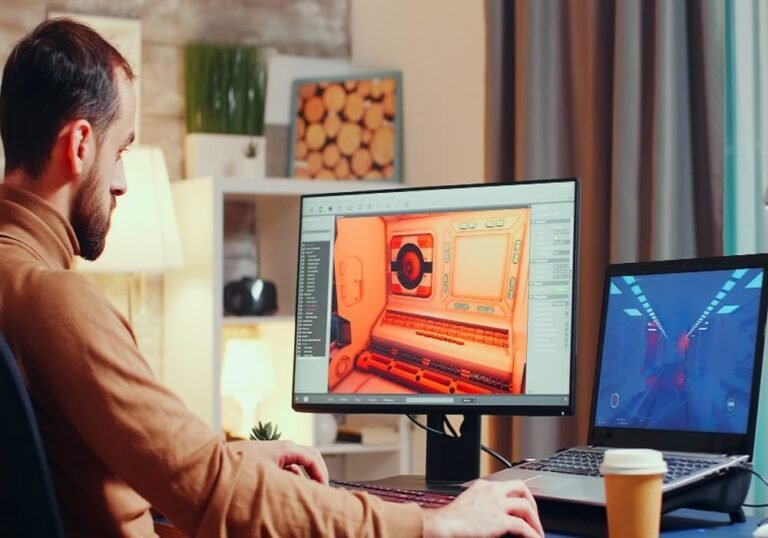

Artists use tools and pressure to achieve variations in tone, from delicate grays to rich blacks. - Digital Art:

Digital artists manipulate brightness and contrast through software tools to enhance realism and design balance.

Emotional and Symbolic Role of Value

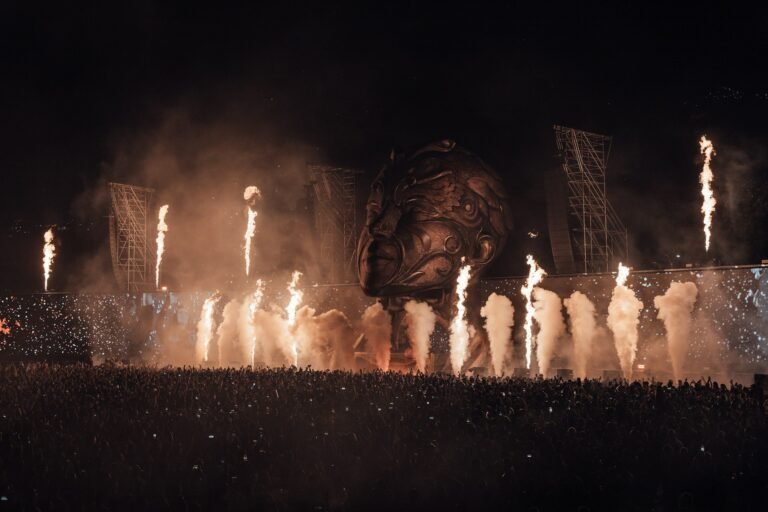

Beyond technical aspects, value has a profound psychological and emotional influence. Light values often convey purity, optimism, and openness, while dark values suggest mystery, power, or sadness. These associations enable artists to create specific atmospheres or emotional responses. For example, a painting dominated by soft light tones might evoke serenity or innocence, while one filled with deep shadows could suggest tension or drama.

Filmmakers and photographers also rely on value to establish mood. A high-key lighting setup (bright with few shadows) creates a cheerful or dreamlike feel, whereas a low-key setup (dark with strong shadows) generates suspense or melancholy. In both visual art and visual storytelling, controlling value equates to controlling emotional tone.

Common Mistakes in Using Value

Many beginners struggle with value because they focus too much on outlines and colors rather than tonal relationships. Common mistakes include:

- Using a limited range of values, resulting in flat images.

- Overblending or failing to maintain distinct light and shadow areas.

- Ignoring the light source, causing inconsistent shading.

- Misjudging color values, leading to poor contrast and visual confusion.

To avoid these errors, artists are encouraged to regularly practice value studies—small sketches that map light and dark patterns before starting a full artwork. These studies train the eye to see tonal differences accurately.

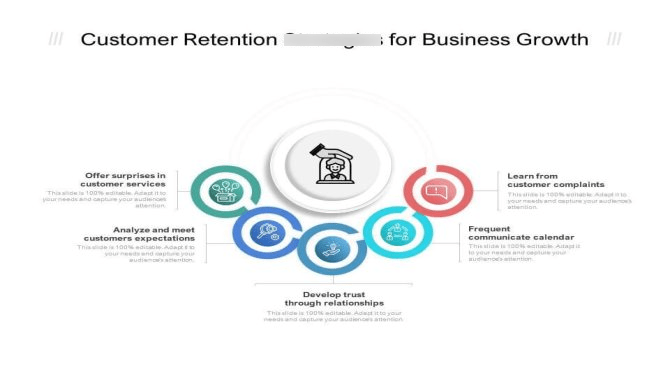

Value and Composition Design

In composition, value acts as a structural framework that guides how the viewer’s eye moves through the artwork. Before even considering subject matter or color, many artists plan a composition in terms of value patterns. By arranging lights and darks strategically, they can control rhythm, balance, and focus. For instance, triangular or circular value arrangements can create stability or movement within a piece.

Strong compositions often display a clear value hierarchy—a dominant light or dark area that captures attention, supported by secondary tones that balance the design. This principle applies universally, whether in classical paintings, graphic design, or modern digital illustration. A well-organized value pattern ensures visual clarity, even when viewed from a distance or in reduced lighting.

Value Studies and Practice

Value studies are small, simplified sketches that artists use to explore tonal relationships before executing a final piece. These studies are typically done in grayscale using pencil, charcoal, or paint. The goal is to identify the distribution of light, mid-tone, and dark areas and ensure a balanced composition. Practicing value studies helps artists improve observational skills and understand how light behaves in real life. Over time, this builds confidence and control, enabling artists to manipulate value intuitively for expressive effect.

Famous Examples of Value in Art

- Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” – Demonstrates subtle value gradations to achieve realistic flesh tones and atmospheric depth.

- Rembrandt’s self-portraits – Use intense contrasts to highlight the face, creating emotional power.

- Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew” – A classic example of chiaroscuro, where a beam of light defines the narrative focus.

- Claude Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” – Shows delicate shifts in value to convey morning mist and reflection.

- Georgia O’Keeffe’s floral paintings – Utilize value transitions to create softness and volume.

These examples reveal how artists across styles and periods use value not just for realism but also for expression.

Conclusion

The value element of art is far more than a simple measure of light and dark; it is a foundational principle that shapes perception, emotion, and structure in every visual medium. Through the intelligent use of value, artists breathe life into flat surfaces, transforming them into spaces filled with form, depth, and atmosphere. Whether in a charcoal sketch, oil painting, or digital composition, value determines how light interacts with form, how space is perceived, and how viewers emotionally connect with an image.

From the dramatic chiaroscuro of the Renaissance to the subtle tonal harmony of modern abstraction, value has remained an essential tool in visual storytelling. It guides the eye, establishes mood, and gives meaning to color and composition. Ultimately, mastering value is mastering vision itself—because to understand value is to understand light, and to understand light is to understand the very essence of art.