Art, as a universal mode of human expression, transcends linguistic and cultural boundaries. Among its myriad forms, geometric art stands out as one of the oldest and most enduring traditions across civilizations. Traditional geometric art, characterized by the use of mathematical precision, symmetry, and repetitive patterns, embodies humanity’s fascination with order, proportion, and beauty. From the mosaics of the Islamic world to the mandalas of South Asia, from ancient Greek pottery to African textiles, geometric art reveals how people across time and space have used abstraction to represent both the physical and metaphysical realms. The significance of this art form lies not only in its aesthetic appeal but also in its philosophical, spiritual, and cultural dimensions. This essay explores the origins, characteristics, cultural expressions, and symbolic meanings of traditional geometric art, highlighting its enduring influence and relevance in the modern world.

Origins of Geometric Art

Geometric art dates back to prehistoric times, long before the invention of writing. Early humans, inspired by natural forms such as shells, crystals, and flowers, began to replicate their inherent symmetry and repetition through carved lines, painted symbols, and woven designs. Archaeological evidence from ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley shows that geometric motifs appeared on pottery, architecture, and textiles thousands of years ago. These early geometric patterns were not merely decorative; they conveyed symbolic meanings, religious beliefs, and cosmic concepts.

In ancient Greece, geometric art flourished during the Geometric Period (900–700 BCE), when artists adorned pottery with linear motifs such as meanders, triangles, and concentric circles. This era marked the transition from purely functional decoration to a structured visual language reflecting harmony and proportion. The Greeks believed that mathematical principles, as articulated by philosophers like Pythagoras and Plato, governed both art and nature. This belief in a geometric cosmos profoundly shaped Western aesthetics and influenced later architectural marvels such as the Parthenon.

Simultaneously, other civilizations cultivated their own geometric traditions. In Egypt, geometric patterns decorated tombs, temples, and jewelry, symbolizing eternal order and divine perfection. The intricate geometries of the Islamic world, developed centuries later, were inspired by both Greek mathematical theory and local spiritual thought, representing a fusion of science and art.

Characteristics of Traditional Geometric Art

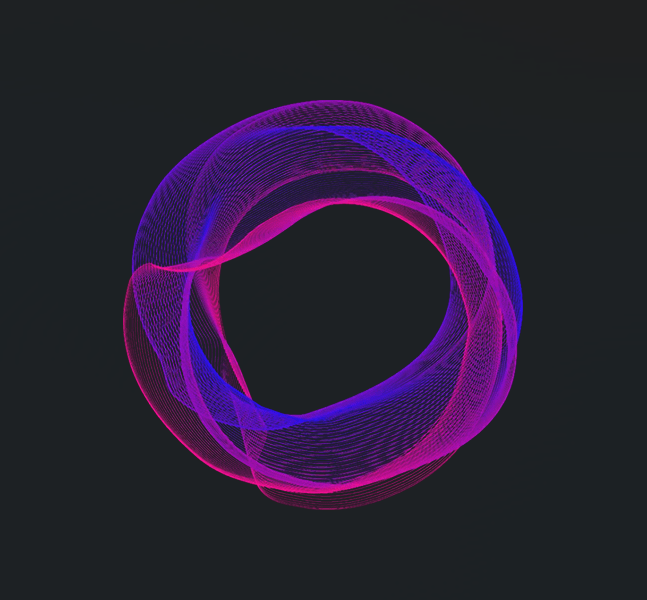

Traditional geometric art is defined by several key characteristics: symmetry, repetition, balance, proportion, and abstraction. These elements combine to create designs that evoke harmony and precision. The patterns are often composed of basic geometric shapes—circles, squares, triangles, and polygons—arranged in complex interlocking forms. The choice of geometry is rarely arbitrary; each shape carries symbolic significance.

Symmetry is a fundamental principle in geometric art, symbolizing balance, harmony, and unity. It can be bilateral, radial, or rotational, depending on cultural context. Repetition reinforces rhythm and order, creating visual continuity that reflects the cyclical nature of existence. Proportion ensures that the relationships between shapes remain consistent, producing an aesthetic that feels both natural and mathematical. Abstraction, meanwhile, distinguishes geometric art from figurative art; rather than depicting living forms directly, it seeks to express universal truths through mathematical forms.

In many traditions, geometric designs are constructed using tools such as a compass and straightedge, reflecting a precise, methodical approach. The process itself often held ritualistic or meditative value. For instance, Islamic artisans constructing geometric patterns began with a circle—representing unity and creation—and divided it into equal segments to generate star-like motifs. The meticulous repetition of patterns was considered a spiritual act, mirroring the infinite perfection of the divine.

Geometric Art in Ancient Civilizations

Geometric art was central to many ancient civilizations, each adapting it to express its own worldview.

In ancient Egypt, geometric principles guided monumental architecture such as pyramids and temples. The pyramid itself is a geometric form symbolizing ascension and the link between earth and heaven. Egyptian artisans also employed geometric designs in decorative arts, using grids to ensure proportionality in wall paintings and reliefs. Their understanding of geometry was deeply tied to cosmic order, or ma’at, representing truth, balance, and harmony.

In Mesopotamia, early cuneiform writing evolved from geometric symbols. Cylinder seals, used for administrative and religious purposes, bore intricate geometric motifs. Similarly, in the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE), excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro have revealed pottery adorned with triangles, circles, and intersecting lines, suggesting both decorative and symbolic functions.

Greek geometric art emphasized mathematical proportion and rational beauty. Pottery from the Geometric Period featured repetitive bands of meanders and zigzags, representing order amid chaos. Later, Greek architects applied geometric ratios to buildings and sculptures, believing these proportions reflected the perfection of the universe. The philosopher Plato famously stated that “God geometrizes continually,” encapsulating the Hellenic reverence for geometry as a divine principle.

In China, geometric motifs appeared in bronzeware, silk textiles, and architecture. The square and circle—representing earth and heaven—formed the foundation of Chinese cosmology, influencing temple design and city planning. The Feng Shui tradition, with its emphasis on spatial balance, also reflects a geometric worldview.

Geometric Art in Islamic Tradition

No discussion of traditional geometric art is complete without acknowledging its pinnacle expression in Islamic art. After the rise of Islam in the 7th century CE, artists and architects sought non-figurative means of expressing divine unity. Islamic theology discouraged the depiction of living beings in sacred spaces, leading artists to turn toward geometry, calligraphy, and arabesque ornamentation.

Islamic geometric art developed into a sophisticated visual language that combined science, mathematics, and spirituality. Artisans used geometric grids to create intricate tiling patterns, known as girih in Persian art, composed of stars, polygons, and interlaced lines. These patterns, often extending infinitely, symbolized the unity of God (Tawhid) and the infinite nature of creation. The circle, often used as the foundational form, represented the perfection of Allah.

Prominent examples include the mosaics of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the tilework of the Alhambra in Spain, and the muqarnas domes of Persian and Ottoman architecture. These masterpieces demonstrate how geometry became a form of visual theology, reflecting divine harmony and order. The mathematical precision of Islamic art also contributed to the advancement of geometry and algebra in the Islamic Golden Age.

Geometric Art in South Asia

In South Asia, geometric art has ancient roots and profound spiritual significance. The mandala, one of the most iconic geometric forms, originates from Hindu and Buddhist traditions. A mandala is a circular diagram representing the universe, used as a tool for meditation and ritual. Its design, based on concentric symmetry, symbolizes the cosmos’ organization around a central point—the axis of existence. Creating or contemplating a mandala is believed to bring spiritual balance and enlightenment.

Indian temples and architecture also reflect geometric precision. The ancient text Vastu Shastra, which governs architectural design, is based on geometric grids known as Vastu Purusha Mandala. Each part of the structure corresponds to cosmic principles, ensuring harmony between human dwellings and the universe. Similarly, in Buddhist stupas and Tibetan thangkas, geometric proportions guide artistic creation to maintain spiritual balance.

Geometric art also appears in South Asian crafts such as rangoli (floor designs), kolam (line drawings), and textile patterns. These designs, created using rice flour or colored powders, are drawn daily at home entrances to welcome prosperity and divine blessings. The act of creating these ephemeral geometric forms connects everyday life to sacred order.

African and Indigenous Geometric Traditions

Across the African continent, geometric art manifests in diverse forms—woven fabrics, beadwork, pottery, and architecture. The repetition of lines, triangles, and spirals often conveys symbolic meanings related to fertility, ancestry, and community. For instance, in Ndebele wall paintings, women decorate houses with bold geometric patterns that communicate identity, social status, and cultural continuity. Similarly, Kente cloth from Ghana uses geometric motifs to represent moral values and historical narratives.

In Islamic North Africa, geometric tilework known as zellige mirrors the mathematical sophistication of Middle Eastern art, combining local craftsmanship with spiritual symbolism. Meanwhile, indigenous peoples of the Americas, such as the Maya, Navajo, and Inca, incorporated geometric motifs into textiles, pottery, and architecture to represent cosmological principles. For the Navajo, for instance, weaving geometric patterns is both an artistic and sacred practice, symbolizing the interconnectedness of all life.

Philosophical and Spiritual Symbolism

Traditional geometric art is far more than decoration—it is a symbolic language expressing metaphysical truths. Geometry, in its purest sense, represents the structure of the universe. Ancient philosophers, including Pythagoras and Plato, viewed geometry as a bridge between the material and spiritual worlds. The precision of geometric forms mirrored the divine order underlying chaos.

The circle often represents unity, eternity, and perfection, as it has no beginning or end. The square symbolizes stability, material existence, and the four elements—earth, water, air, and fire. The triangle signifies harmony, balance, and the trinity found in many spiritual traditions. Hexagons, found in Islamic mosaics and natural forms like honeycombs, symbolize harmony and cooperation. The spiral, recurring in indigenous art, embodies growth, evolution, and the cyclical nature of life.

In sacred geometry—a philosophical system uniting mathematics and spirituality—geometric forms are seen as archetypes of creation. The Flower of Life, for example, consists of overlapping circles forming a hexagonal pattern, representing the interconnectedness of all living things. Sacred geometry underlies architectural masterpieces like the Great Pyramid of Giza, Chartres Cathedral, and Borobudur Temple, all constructed according to precise geometric ratios believed to channel cosmic energy.

Cultural and Aesthetic Significance

The significance of traditional geometric art extends beyond spirituality to encompass cultural identity, communication, and aesthetics. Geometric motifs serve as visual markers of cultural heritage, passed down through generations in textiles, pottery, and architecture. Each culture infuses geometry with unique meanings, adapting it to local materials and worldviews.

Aesthetically, geometric art embodies a universal sense of beauty derived from order and proportion. The human brain naturally perceives symmetry and repetition as pleasing, suggesting that our attraction to geometry may be biologically rooted. Geometric designs also reflect intellectual achievement—the ability to abstract, calculate, and construct complex systems from simple forms.

Culturally, geometric art functions as a unifying language. While styles differ across regions, the shared reliance on mathematical principles links diverse civilizations. This universality fosters cross-cultural dialogue, showing how geometry transcends religion and geography.

Transmission and Continuity

The transmission of geometric art has occurred through both formal education and oral traditions. Ancient guilds, such as those of Islamic artisans or Hindu temple architects, preserved geometric knowledge through apprenticeships. Patterns were often drawn on parchment, tiles, or wooden templates, serving as models for future generations.

Colonialism and modernization disrupted many traditional art forms, yet geometric art has proven resilient. In the 20th century, modern artists such as Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, and Frank Stella revived geometric abstraction, inspired by traditional motifs but reinterpreted through modernism. Similarly, contemporary designers incorporate geometric principles into digital art, architecture, and fashion, bridging ancient wisdom with technological innovation.

Geometric Art in Modern Design and Architecture

Modern architecture continues to draw from traditional geometric art. Architects like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright used geometric order to achieve balance between structure and aesthetics. Islamic geometry influenced the design of modern mosques and public spaces, where traditional patterns are reimagined using contemporary materials like glass and steel.

In design, geometric patterns dominate graphic arts, textiles, and digital interfaces. The resurgence of mandala art in mindfulness culture, the use of tessellations in modern tiling, and the minimalist geometry of corporate logos all demonstrate the continued appeal of geometric aesthetics. The digital age, with its reliance on algorithms and vector graphics, mirrors the same principles of proportion and repetition found in ancient designs.

Educational and Scientific Value

Beyond its cultural and aesthetic roles, traditional geometric art holds educational and scientific significance. It offers insight into early mathematical knowledge, spatial reasoning, and architectural engineering. The study of Islamic tiling patterns, for example, has revealed sophisticated use of quasi-crystalline geometry centuries before its formal discovery in modern mathematics. Similarly, traditional crafts like weaving and basketry embody algorithmic thinking, symmetry operations, and fractal geometry.

In education, geometric art provides an interdisciplinary bridge between mathematics, art, and cultural studies. By exploring geometric designs, students can understand both abstract mathematical principles and their cultural expressions, fostering holistic learning.

Preservation and Global Appreciation

Today, global institutions and cultural organizations recognize the need to preserve traditional geometric art. UNESCO has designated several geometric art forms as Intangible Cultural Heritage, including Moroccan zellige tilework and Indian kolam drawing. Museums, digital archives, and community workshops document and teach these traditions, ensuring their survival in the modern world.

The global appreciation of geometric art also promotes intercultural understanding. Exhibitions showcasing Islamic, African, and Asian geometric patterns highlight shared human values—order, beauty, and spirituality. This recognition underscores geometry’s role as a universal artistic language that unites rather than divides.

Conclusion

Traditional geometric art is a profound testament to humanity’s quest for order, meaning, and beauty. Rooted in ancient civilizations yet continually reinvented, it transcends cultural boundaries to express universal truths. Through geometry, artists have mirrored the cosmos, symbolized divinity, and encoded philosophical ideas into visual form. Its significance lies not only in its mathematical precision or aesthetic elegance but in its capacity to connect the material and spiritual realms.

From the sacred mandalas of India to the intricate tilework of the Alhambra, from African textiles to modern architecture, geometric art remains a living tradition—ever evolving, yet eternally grounded in the same principles that inspired our ancestors. In a fragmented modern world, the timeless harmony of geometric art continues to remind us of the unity that underlies all existence.