Gothic art is one of the most remarkable and transformative artistic movements in European history. Emerging in the mid-12th century and flourishing until the 16th century, it represented a powerful evolution from the earlier Romanesque style. It was not only an artistic style but a profound expression of medieval European culture, spirituality, and intellect. Gothic art embodied the spirit of the Middle Ages—a time of religious devotion, architectural innovation, and growing civic pride. It touched multiple disciplines, including architecture, sculpture, painting, stained glass, and manuscript illumination. While it was rooted in Christian theology and designed primarily to glorify God, Gothic art also reflected the social, political, and philosophical changes of its time. Its importance in art history lies not only in its aesthetic grandeur but also in the way it transformed the perception of space, light, and emotion in art.

Origins and Development of Gothic Art

The term “Gothic” was first coined during the Renaissance, originally as a derogatory term used by Italian humanists to describe what they considered the barbaric art of the Goths—a Germanic tribe that had contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire. However, in reality, Gothic art had little to do with the Goths. It emerged in France around the 1140s, particularly in the Île-de-France region, under the patronage of Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis. The rebuilding of the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis near Paris is widely regarded as the birth of the Gothic style. Abbot Suger sought to create a church that embodied the divine light of God, a “lux nova” that would elevate the human soul toward heaven. This idea of light became the defining feature of Gothic art and architecture.

From France, the Gothic style spread across Europe, evolving into different regional variations. In England, it became known for its linear grace and elaborate fan vaults; in Germany, for its soaring verticality; in Italy, for its integration of classical elements and rich decoration. By the 13th and 14th centuries, Gothic art dominated European visual culture, influencing cathedrals, civic buildings, and religious artworks across the continent. It continued to evolve into the late Gothic and flamboyant Gothic styles, which became increasingly ornate and expressive before gradually giving way to the Renaissance.

Characteristics of Gothic Architecture

Architecture was the foundation of Gothic art, and its innovations were both technical and symbolic. The main characteristics of Gothic architecture include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, and the flying buttress. These structural innovations allowed architects to build taller and lighter buildings, with vast interior spaces filled with stained glass windows that filtered divine light into the sacred environment. The pointed arch distributed weight more efficiently than the round Romanesque arch, allowing for greater height and flexibility in design. The ribbed vault reinforced ceilings, while the flying buttress transferred the weight of the roof away from the walls, making it possible to open large areas for windows.

The result was an architecture that seemed to defy gravity, drawing the eyes upward in an expression of spiritual aspiration. Cathedrals such as Notre-Dame de Paris, Chartres Cathedral, and Amiens Cathedral stand as masterpieces of this architectural ingenuity. Their soaring spires, intricate tracery, and radiant stained glass were designed to inspire awe and devotion. The interior spaces of these buildings became vast sanctuaries of light and color, transforming the experience of worship into a visual and emotional journey toward the divine.

Sculpture in Gothic Art

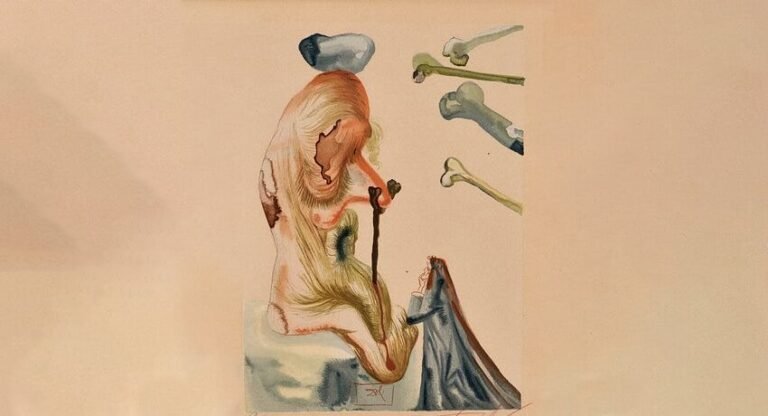

Gothic sculpture developed alongside architecture, often serving as an integral decorative and didactic element of cathedrals. The façades of Gothic cathedrals were adorned with thousands of sculptural figures—saints, angels, prophets, and biblical scenes—that served to instruct and inspire the faithful. Unlike the rigid, abstract figures of the Romanesque style, Gothic sculpture displayed a new naturalism and emotional depth. Figures were given lifelike proportions, graceful poses, and expressive faces that conveyed spiritual intensity.

For example, the Portal of the Virgin at Chartres Cathedral or the Royal Portal of the Cathedral of Amiens show how sculptors combined theological symbolism with human expression. The figures are elongated and elegant, yet their gestures and facial expressions convey compassion, serenity, and divine grace. Later Gothic sculpture, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries, became even more expressive and dynamic, reflecting a growing interest in human emotion and realism. This development paved the way for the naturalism of Renaissance sculpture.

Stained Glass and the Role of Light

One of the most iconic features of Gothic art is stained glass. It served both a decorative and a didactic function, transforming church interiors into kaleidoscopes of colored light while illustrating biblical stories for an illiterate congregation. Stained glass windows were not merely decorative; they were considered manifestations of divine light. The idea, deeply rooted in medieval theology, was that light passing through colored glass represented the presence of God illuminating the world through spiritual truth.

The windows of Chartres Cathedral, Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and York Minster are among the finest examples. They depict scenes from the Bible, the lives of saints, and moral allegories, all rendered in vivid blues, reds, and golds. The play of light within the cathedral created an atmosphere of transcendence, reinforcing the sense of being in a heavenly realm. The artistry required to design and produce these windows—combining glassmaking, painting, and leadwork—was extraordinary, and stained glass became one of the highest art forms of the Gothic era.

Gothic Painting and Manuscript Illumination

While architecture and sculpture were dominant, painting and manuscript illumination also flourished during the Gothic period. Early Gothic painting was largely confined to religious manuscripts produced by monastic scribes. These illuminated manuscripts were richly decorated with gold leaf, intricate borders, and miniature scenes depicting biblical events. Over time, as universities and urban centers grew, manuscript production became more secularized, and lay artists and workshops began to flourish.

By the 13th and 14th centuries, panel painting began to develop as an independent art form. Gothic painters such as Giotto di Bondone in Italy introduced greater realism, depth, and emotion into their work, bridging the gap between medieval stylization and Renaissance naturalism. Giotto’s frescoes in the Arena Chapel in Padua, for instance, show a revolutionary understanding of human emotion and spatial perspective. In Northern Europe, painters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden later built on these foundations, developing the early Northern Renaissance style with their attention to detail and mastery of oil paint.

Religious and Philosophical Significance

The Gothic style was not merely an artistic movement; it was a manifestation of the medieval worldview. The 12th and 13th centuries were marked by the rise of scholasticism—a philosophical and theological movement that sought to reconcile faith and reason, particularly through the works of thinkers like Thomas Aquinas. Gothic architecture and art reflected this intellectual climate. The design of cathedrals mirrored the rational order and harmony of God’s creation. The careful geometric planning, symbolic proportions, and luminous spaces were visual expressions of divine order and spiritual truth.

Every element of a Gothic cathedral had symbolic meaning. The vertical lines represented the soul’s ascent to heaven; the light filtering through stained glass symbolized divine grace; the cruciform plan of many churches reflected Christ’s sacrifice. Sculpture and painting served as “Bibles in stone and glass,” teaching moral and theological lessons to those who could not read. Thus, Gothic art was deeply didactic, aiming to instruct the faithful and to glorify God through beauty and light.

Social and Cultural Context

Gothic art also reflected broader social changes in medieval Europe. The rise of cities, the growth of trade, and the emergence of a wealthy merchant class led to new forms of artistic patronage. Cathedrals were not only religious centers but also civic symbols, representing the pride and unity of the local community. Towns competed to build the tallest and most magnificent cathedrals, seeing them as both acts of devotion and demonstrations of prosperity.

Guilds of stonemasons, glassmakers, and sculptors flourished, developing sophisticated techniques and standards of craftsmanship. The collaboration between architects, artisans, and theologians gave Gothic art its unique synthesis of faith, intellect, and technical skill. As the Middle Ages progressed, secular themes began to appear more frequently in art, reflecting the growing complexity of medieval society. This diversification of subject matter laid the groundwork for the humanism of the Renaissance.

Regional Variations of Gothic Art

As the Gothic style spread across Europe, it evolved in distinctive regional ways. In France, the birthplace of Gothic art, the emphasis was on verticality, harmony, and light. Cathedrals such as Reims, Amiens, and Chartres exemplify the classic French High Gothic style, with balanced proportions and extensive use of stained glass.

In England, Gothic architecture developed through several phases—from Early English to Decorated and Perpendicular Gothic. English cathedrals like Salisbury, Canterbury, and York Minster are known for their long, horizontal lines and elaborate vaulting systems. The fan vaulting of King’s College Chapel in Cambridge represents one of the most exquisite examples of late Gothic design.

In Germany and Central Europe, the Gothic style was characterized by extreme verticality and intricate ornamentation, as seen in Cologne Cathedral. In Italy, Gothic art merged with classical traditions. Italian cathedrals such as Orvieto, Siena, and Milan Cathedral combined Gothic structural features with colorful marble façades and humanistic decoration. Italian Gothic painting, led by Giotto, Duccio, and Simone Martini, introduced emotional realism and narrative clarity that profoundly influenced later European art.

Late Gothic and the Transition to the Renaissance

By the 15th century, Gothic art had reached its most ornate phase, often referred to as Flamboyant Gothic in France and Perpendicular Gothic in England. This period was characterized by intricate tracery, elaborate decoration, and an almost lace-like treatment of stone. While still deeply rooted in religious tradition, late Gothic art began to reflect a growing interest in human experience and worldly beauty.

The late Gothic period overlapped with the early Renaissance, and the transition between the two styles was gradual. Artists such as Claus Sluter in Burgundy introduced a heightened realism and emotional power in sculpture that anticipated Renaissance naturalism. Meanwhile, the invention of oil painting in Northern Europe allowed artists to achieve unprecedented detail and luminosity. By the 16th century, the ideals of classical harmony and humanism had largely replaced the spiritual transcendence of Gothic art, yet the influence of Gothic innovation endured.

The Legacy and Importance of Gothic Art

The importance of Gothic art in art history cannot be overstated. It marked a turning point in the Western artistic tradition—introducing new ways of thinking about space, light, and emotion. Architecturally, it represented one of the greatest achievements of human creativity. The structural solutions developed by Gothic architects paved the way for modern engineering, while the aesthetic principles of verticality and light continue to inspire contemporary architecture.

Artistically, Gothic art bridged the gap between the symbolic abstraction of the Romanesque and the realism of the Renaissance. Its emphasis on naturalism, human expression, and narrative storytelling laid the foundation for later artistic developments. Culturally, Gothic art expressed the values and aspirations of medieval society—its faith, its intellect, and its communal identity. It was a synthesis of art, science, and spirituality, reflecting a worldview in which beauty was inseparable from divine truth.

In the 19th century, during the Gothic Revival, artists and architects such as Augustus Pugin, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, and John Ruskin rediscovered the beauty and craftsmanship of the medieval style. They saw in Gothic art a moral and aesthetic ideal that contrasted with the industrialization and materialism of modern society. This revival reaffirmed the timeless appeal of Gothic aesthetics and their continuing relevance to artistic expression.

Conclusion

Gothic art stands as one of the crowning achievements of human civilization—a synthesis of faith, intellect, and artistic genius. It transformed the physical and spiritual landscape of medieval Europe and left a legacy that endures in the cathedrals, sculptures, and paintings that still inspire awe today. Its importance lies not only in its aesthetic beauty but in its ability to express profound spiritual truths through form, light, and color. Gothic art reminds us that art is not merely decoration but a reflection of the human spirit striving toward the divine. By elevating the material to the spiritual, the Gothic style captured the essence of the medieval imagination and shaped the course of Western art for centuries to come.