Alternating Rhythm in Art: An In-Depth Exploration

Introduction

In the visual arts, rhythm plays a central role in shaping how viewers perceive and engage with a work. Just as rhythm structures the movement of music or poetry, rhythm in art creates a sense of flow, direction, and order. It guides the eye across a canvas, a sculpture, or even an architectural façade. Among the various types of rhythm used by artists—such as regular, flowing, progressive, and random—alternating rhythm holds a particularly distinctive place. Alternating rhythm refers to the deliberate repetition of elements in a back-and-forth sequence, often producing a sense of variation within repetition. This oscillation of visual elements captures attention and stimulates interest, preventing monotony while still maintaining coherence. To understand alternating rhythm in art, it is essential to examine its definition, its significance, and concrete examples where it has been applied effectively.

One of the most accessible and compelling examples of alternating rhythm can be found in architectural ornamentation, where columns, arches, or decorative motifs repeat in a pattern that alternates in size, shape, or color. A well-known instance occurs in the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, where Islamic geometric patterns employ alternating rhythm to create both visual harmony and spiritual symbolism. Similarly, in painting, artists such as Piet Mondrian or Victor Vasarely employed alternating rhythm in their abstract works to create dynamic compositions that continue to fascinate viewers. To ground this discussion, this essay will consider alternating rhythm as a principle of design, provide an extensive explanation of its psychological effects, and analyze specific examples from both historical and modern art.

Understanding Rhythm in Visual Art

Before focusing specifically on alternating rhythm, it is useful to outline what rhythm means in visual art. Rhythm, in essence, is the visual tempo created by the recurrence of elements such as line, shape, color, or texture. When an artist repeats these elements in an organized fashion, rhythm emerges. The viewer’s gaze does not remain static; instead, it moves along the repeating features, much as the ear follows the beat in music.

Art historians and educators often categorize rhythm into different types:

- Regular rhythm: Identical elements repeat in consistent intervals.

- Flowing rhythm: Elements repeat in organic, wave-like sequences, often resembling natural patterns.

- Progressive rhythm: Repetition occurs with gradual changes, such as shapes increasing in size or colors shifting in tone.

- Random rhythm: Repetition is present but without clear order, producing spontaneity.

- Alternating rhythm: Two or more elements repeat in an alternating fashion, creating contrast and variation within a predictable structure.

Alternating rhythm stands out because it combines the reliability of repetition with the visual stimulation of difference. Unlike regular rhythm, which can sometimes appear static or monotonous, alternating rhythm keeps the eye alert, anticipating change with each iteration.

Defining Alternating Rhythm

Alternating rhythm occurs when an artist establishes a back-and-forth sequence using at least two distinct elements. These elements might be contrasting colors (black and white), different shapes (square and circle), or varied sizes (large and small). The alternation can be simple—such as a checkerboard pattern—or complex, where several visual components alternate in layered sequences.

The power of alternating rhythm lies in its ability to balance stability and movement. On one hand, the repetition provides order, making the work cohesive. On the other hand, the alternation injects variety, preventing visual fatigue. This principle has been applied across cultures and mediums, from ancient mosaics to contemporary graphic design, because it appeals to a fundamental human appreciation for patterns with variation.

Psychological and Aesthetic Effects

Alternating rhythm has profound effects on how a viewer experiences a piece of art:

- Engagement: The alternating sequence keeps the viewer’s eye moving across the composition, ensuring sustained attention.

- Anticipation: The brain naturally predicts patterns. When elements alternate, the viewer anticipates the next switch, creating subtle excitement.

- Balance and Contrast: Alternating rhythm often juxtaposes opposites, such as light and dark or curved and angular. This contrast sharpens perception and adds dynamism.

- Symbolism: In some traditions, alternation has symbolic meaning. For example, alternating black and white tiles in Islamic or medieval architecture can symbolize dualities such as day and night, earthly and divine, or life and death.

The universality of alternating rhythm suggests it resonates with cognitive tendencies toward recognizing patterns and finding meaning in contrasts.

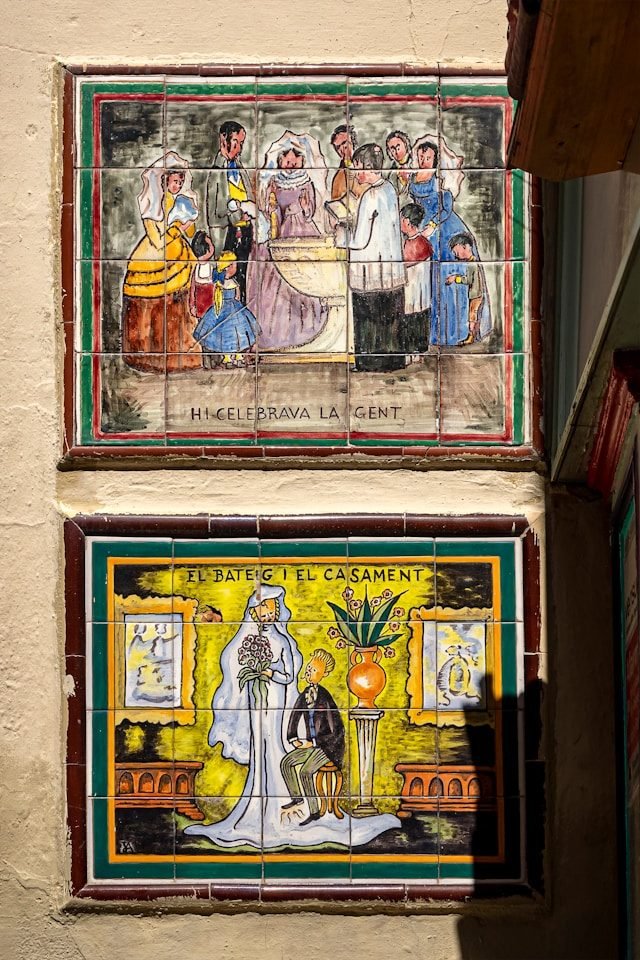

Historical Example: Alternating Rhythm in Islamic Art

One of the richest historical contexts for alternating rhythm is Islamic decorative art, particularly in architecture. Because Islamic tradition often discouraged figural representation in sacred spaces, artists turned to abstract geometry and vegetal motifs. Alternating rhythm became a key organizing principle in tiling, calligraphy, and stucco work.

Consider the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. Built in the 13th and 14th centuries, its walls and ceilings are covered with intricate geometric patterns where alternating colors, shapes, and motifs produce a mesmerizing effect. For example, a band of tiles may alternate between blue and white stars, or between interlacing polygons and floral motifs. This alternation is not random but carefully calculated, reflecting mathematical precision and spiritual symbolism. The alternating rhythm not only beautifies the architecture but also creates a contemplative atmosphere, inviting viewers to reflect on infinity, unity, and divine order.

Example in Painting: Piet Mondrian’s Compositions

In the 20th century, alternating rhythm became central to the works of abstract painters. A clear example comes from Piet Mondrian, a Dutch painter associated with the De Stijl movement. Mondrian’s compositions, such as Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930), rely heavily on alternating rhythm. The painting presents a grid of black lines enclosing rectangles of primary colors and white spaces. The alternation between colored and non-colored blocks, as well as between vertical and horizontal lines, establishes a rhythmic pulse across the canvas.

Unlike the ornamental complexity of the Alhambra, Mondrian’s alternating rhythm is minimalist, modern, and rational. Yet the psychological effect is similar: the eye moves continuously across the surface, guided by alternating contrasts. The work’s harmony lies not in uniformity but in a carefully calibrated sequence of differences.

Case Study: Victor Vasarely and Op Art

For a more immersive example of alternating rhythm, consider Victor Vasarely, often regarded as the father of Op Art (Optical Art). His works from the mid-20th century exploit alternating rhythm to create visual illusions of depth and movement.

Take the painting Vega-Nor (1969). Here, Vasarely employs a grid of alternating colored squares that seem to bulge outward, as if the canvas itself is pulsating. The alternating rhythm of the colors—dark and light, warm and cool—creates a sense of vibration that tricks the eye into perceiving three-dimensional form. In this case, alternating rhythm does more than engage the eye; it destabilizes perception itself, making the viewer aware of how rhythm can manipulate visual experience.

Alternating Rhythm in Sculpture and Architecture

Beyond two-dimensional art, alternating rhythm is equally significant in sculpture and architecture. The Parthenon in Athens, for example, employs an alternating sequence of triglyphs and metopes across its frieze. This back-and-forth pattern establishes visual order while also accommodating narrative scenes in the metopes. Similarly, Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals often use alternating columns or arches along their naves, creating a steady rhythm that both guides the eye toward the altar and reinforces the sacred atmosphere.

In sculpture, alternating rhythm can be found in works where forms repeat with variation. For example, Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell features alternating figures and spaces, creating a sense of pulsating movement across the monumental bronze doors.

Alternating Rhythm in Modern and Contemporary Art

In contemporary practice, alternating rhythm remains central, particularly in graphic design, installation art, and digital media. Designers frequently employ alternating patterns in posters, logos, and websites because they are visually striking and easy to process. Installation artists, such as Yayoi Kusama, also exploit alternating rhythm by filling spaces with polka dots or mirrored surfaces, producing immersive environments where alternation becomes overwhelming and surreal.

Digital artists further expand on alternating rhythm by animating it. Alternating sequences can now change dynamically over time, creating not only spatial but temporal rhythm. This dynamic alternation is foundational to visual effects in film, animation, and interactive art.

Why Alternating Rhythm Matters

The importance of alternating rhythm in art cannot be overstated. It exemplifies the broader principle that human beings are drawn to both repetition and difference. Complete uniformity bores the eye, while complete randomness overwhelms it. Alternating rhythm occupies the sweet spot, providing just enough predictability to orient the viewer and just enough variation to maintain interest.

Moreover, alternating rhythm reflects a fundamental truth about existence: life itself is a cycle of alternations—day and night, inhalation and exhalation, activity and rest. When artists use alternating rhythm, they are not merely designing visually appealing works; they are echoing natural and existential patterns.

Conclusion

Alternating rhythm in art, as a principle of design, is one of the most enduring and versatile tools in an artist’s repertoire. From the geometric tiles of the Alhambra to the minimalist grids of Mondrian, from the optical illusions of Vasarely to the immersive installations of Kusama, alternating rhythm demonstrates its power across cultures, centuries, and mediums. It engages the eye, stimulates the mind, and resonates with deep-seated human experiences of pattern and variation.

By alternating elements in a deliberate sequence, artists achieve a balance between order and diversity, predictability and surprise. This is why alternating rhythm continues to captivate audiences and why it remains a vital concept in art education and practice. In sum, alternating rhythm is not merely a stylistic choice but a profound expression of how humans perceive, interpret, and find beauty in the world.