Pre-Raphaelite art refers to a distinctive movement that emerged in mid-19th-century Britain, led by a group of young artists who sought to reform the prevailing artistic conventions of their time. Officially founded in 1848, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) consisted of seven founding members—William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, James Collinson, Thomas Woolner, Frederic George Stephens, and William Michael Rossetti. This collective of painters, poets, and critics was deeply dissatisfied with what they perceived as the formulaic and superficial art promoted by the Royal Academy, particularly the style derived from the Renaissance master Raphael. They believed that art had become artificial and divorced from truth and nature. Thus, the PRB proposed a return to the detail, intensity, and complexity found in art before Raphael, particularly that of the Quattrocento (early Italian Renaissance) painters such as Sandro Botticelli and Jan van Eyck. This radical approach not only redefined Victorian aesthetics but also created a body of work that still fascinates modern audiences with its richness, symbolism, and emotional depth.

At its core, Pre-Raphaelite art is characterized by meticulous attention to detail, brilliant color palettes, and an emphasis on realism. The artists sought to represent the natural world with precision and vibrancy, often painting directly from life and using intense natural light. Their paintings stand out for their vivid hues and the almost photographic quality of their textures—whether in the shimmering fabrics, the intricate backgrounds, or the expressive faces of their subjects. A key technical innovation of the PRB was their use of a white ground on the canvas, over which translucent colors were layered to achieve luminous effects. This approach contrasted sharply with the dark, muted tones prevalent in academic painting at the time and helped to create the distinctive visual intensity associated with the Pre-Raphaelites.

One of the central themes of Pre-Raphaelite art is medievalism and romantic idealism. The artists were inspired by the literature, legends, and aesthetics of the Middle Ages, which they saw as a purer, more sincere era, untainted by the industrialization and moral ambiguity of their own time. They frequently depicted scenes from Arthurian legend, medieval romances, and early Christian narratives. For example, Millais’s Isabella (1849) was inspired by a story from Boccaccio’s Decameron, while Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel (1871–78) drew on Dante’s La Vita Nuova. These works portray a world of chivalry, spiritual love, and high moral ideals, infused with sensual beauty and emotional depth. The Pre-Raphaelites did not merely romanticize the past; they reimagined it as a realm of moral clarity and aesthetic richness, contrasting it with the corruption and utilitarianism of Victorian society.

Another dominant theme is the celebration of nature and truth to nature, reflecting the influence of John Ruskin, a prominent art critic and supporter of the Brotherhood. Ruskin championed the idea that art should faithfully depict the natural world, and he believed that truth to nature was both a moral and aesthetic imperative. The Pre-Raphaelites took this to heart, often painting en plein air and paying close attention to botanical accuracy and landscape details. In works like Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd (1851) or Millais’s Ophelia (1851–52), every flower, leaf, and blade of grass is rendered with scientific precision, yet the overall effect is poetic and emotionally resonant. The natural world, in Pre-Raphaelite painting, is not merely a backdrop but a vital, living presence imbued with symbolic and spiritual meaning.

Religion and spirituality also feature prominently in Pre-Raphaelite art, particularly in the early works of the Brotherhood. These artists were deeply engaged with questions of faith, morality, and redemption, and they often turned to biblical stories or Christian symbolism to explore these themes. For instance, Hunt’s The Light of the World (1851–53) is a deeply allegorical painting that portrays Christ knocking on a door that represents the human soul. The painting is filled with symbolic detail, from the overgrown plants indicating neglect to the rusted hinges suggesting long disuse. Hunt’s treatment of religious subjects was both innovative and deeply personal, reflecting his belief in the spiritual power of art. However, unlike traditional religious painting, the Pre-Raphaelite approach was not didactic or orthodox; rather, it was infused with psychological depth and individual interpretation, allowing for a more intimate and contemplative experience.

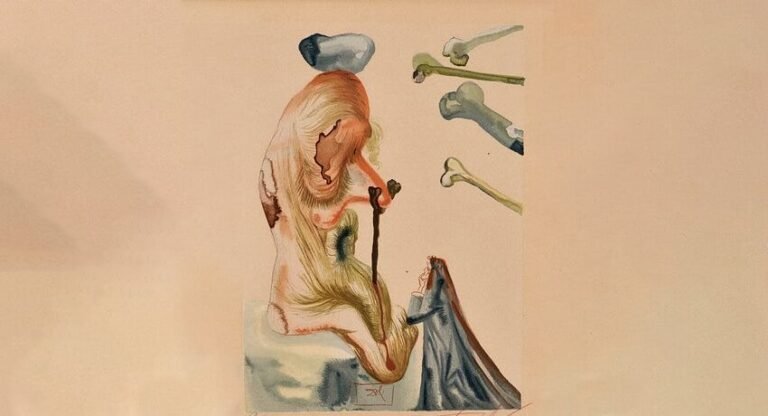

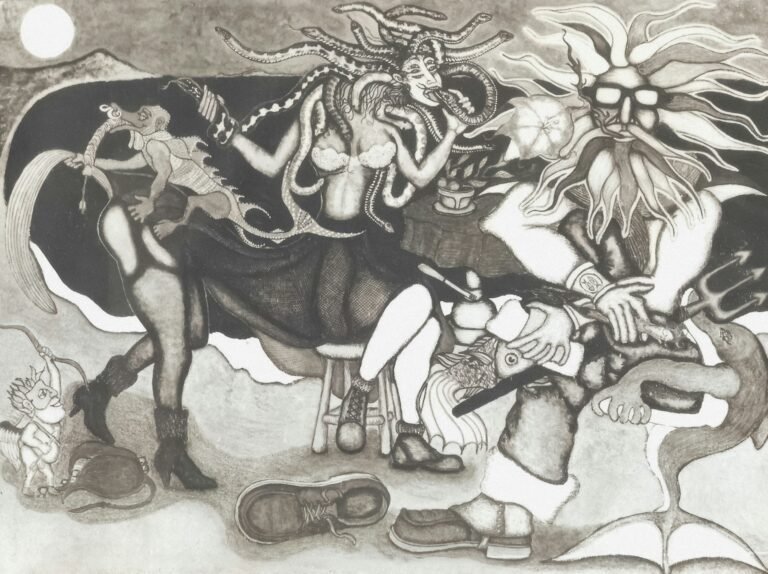

The role of women in Pre-Raphaelite art is one of its most discussed and complex aspects. Pre-Raphaelite artists were fascinated by feminine beauty, mystique, and emotional expressiveness, and women feature prominently in their compositions. These women are often portrayed not as passive muses but as central figures imbued with agency, sensuality, and inner turmoil. The recurring figure of the tragic or ethereal woman—such as Millais’s Ophelia, Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, or Burne-Jones’s Laus Veneris—is a hallmark of the style. Rossetti, in particular, created an archetype of the “Pre-Raphaelite beauty,” characterized by long flowing hair, large expressive eyes, and a languid, dreamlike presence. His models, including Elizabeth Siddal, Jane Morris, and Fanny Cornforth, became icons of this aesthetic. However, these representations have also been critiqued for their idealization and objectification of women, raising questions about the boundary between admiration and control. Some later Pre-Raphaelite works also engage with the figure of the femme fatale or fallen woman, reflecting Victorian anxieties about sexuality, purity, and female independence.

Literature and poetry were integral to the Pre-Raphaelite imagination. Many of the artists were also poets, especially Rossetti, who published his own poetry and frequently illustrated literary texts. The interplay between visual and literary art was central to the movement’s ethos. Paintings were often inspired by or directly referenced poetic works, while their titles and accompanying verses added layers of meaning. For example, Rossetti’s painting Proserpine was accompanied by a sonnet that deepened the mythological and psychological resonance of the image. The influence of poets such as Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Alfred Tennyson, and John Keats is evident in many Pre-Raphaelite works. Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, in particular, became a rich source of imagery and allegory for artists like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, who sought to visualize the noble ideals and tragic fates depicted in these narratives. This blending of text and image exemplified the Pre-Raphaelite aim of synthesizing different art forms into a unified expression of beauty and truth.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though initially united by a common vision, gradually evolved into different strands and styles. The early members eventually took divergent paths, with Hunt remaining committed to moralistic realism, Millais transitioning to a more conventional academic style, and Rossetti moving toward a more symbolist and sensual aesthetic. This latter development marked the emergence of the so-called second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, which included artists like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. These later Pre-Raphaelites were more decorative, symbolic, and mythological in their approach, laying the groundwork for the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau. Their works were less concerned with realism and more focused on the evocative power of line, color, and form. Burne-Jones’s dreamlike canvases, filled with languid figures and enchanted landscapes, created an otherworldly vision that moved beyond historical accuracy or moral narrative into the realm of pure fantasy and emotional suggestion.

The themes of love and loss also run deeply through Pre-Raphaelite art, particularly in the works of Rossetti. His personal life—marked by the tragic death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal—influenced many of his later paintings and poems, which dwell on memory, mourning, and the spiritual bond between lovers. His Beata Beatrix (1864–70) is a moving tribute to Siddal, drawing on Dante’s idealized love for Beatrice to create a vision that is both romantic and elegiac. Similarly, Dante’s Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice (1871) explores themes of ideal love transcending death, using a rich tapestry of symbols, colors, and gestures to evoke a sense of spiritual longing. Such works exemplify the Pre-Raphaelite fascination with beauty that endures beyond the material world, as well as the emotional complexity of human relationships.

Another significant theme is social critique and commentary, particularly in the early works of Hunt and Millais. Although the Pre-Raphaelites are often associated with escapist medievalism, some of their paintings engage directly with the social realities of Victorian England. Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853) depicts a young woman suddenly realizing the moral implications of her role as a kept mistress, while Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents (1850) controversially portrayed the Holy Family in a humble carpenter’s workshop with realistic grime and poverty. These works challenged Victorian sensibilities and exposed the tensions between religious idealism and social reality. In this way, Pre-Raphaelite art could function not only as a retreat from modernity but also as a mirror held up to its hypocrisies and injustices.

The Pre-Raphaelite movement also had a profound influence on design and decorative arts, particularly through the work of William Morris. A socialist and craftsman, Morris believed that art should be part of everyday life and accessible to all. He founded the firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (later Morris & Co.), which produced wallpapers, textiles, stained glass, and furniture inspired by Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics and medieval craftsmanship. This fusion of art and design reflected the Brotherhood’s holistic vision of beauty and truth, which extended beyond painting into poetry, architecture, and home decoration. The movement’s influence can thus be seen in the broader Arts and Crafts Movement, which emphasized handmade quality, artistic integrity, and the integration of art into daily life.

Despite initial criticism and misunderstanding from the academic establishment, the legacy of Pre-Raphaelite art has endured. In the 20th and 21st centuries, it has been re-evaluated and celebrated for its originality, technical brilliance, and emotional intensity. Modern scholars and viewers alike have recognized the movement’s role in challenging the conventions of its time, bridging the gap between Romanticism and Modernism, and exploring themes that remain relevant—love, loss, nature, faith, gender, and beauty. Its artists were ahead of their time in many ways, anticipating the symbolist, surrealist, and even feminist discourses that would emerge in later art movements. The Pre-Raphaelites left behind a body of work that not only captures the spirit of a bygone era but also continues to inspire and resonate with audiences today.

In conclusion, Pre-Raphaelite art was more than a stylistic rebellion against academic norms; it was a profound reimagining of what art could be—morally earnest, emotionally rich, and sensually beautiful. Through themes of medievalism, nature, spirituality, literature, love, and social conscience, the Pre-Raphaelites created a visual and intellectual legacy that transcends their historical moment. Their meticulous technique, poetic imagination, and passionate belief in art’s transformative power have ensured their lasting place in the history of Western art. Whether through the haunting gaze of a Rossetti muse, the crystalline waters of Millais’s landscapes, or the jewel-toned tapestries of Morris, Pre-Raphaelite art invites us to see the world with new eyes—eyes attuned to beauty, truth, and the eternal dance between the real and the ideal.